-

15-year-old boy murdered by Israeli forces

20th March 2014 | International Solidarity Movement, Khalil Team | Hebron, Occupied Palestine Early yesterday morning, 15-year-old Yousef Shawamri was shot dead by Israeli soldiers near the village of Deir Al-Asal al Fauqa. Yousef and two of his friends were trying to pass though a hole in a wire fence to reach Palestinian land that […]

-

Prisoner released leads to celebrations in Awarta

18th March 2014 | International Solidarity Movement, Nablus Team | Awarta, Occupied Palestine Yesterday in the village of Awarta, 26-year-old Rais Abdat was released from an Israeli prison. Three years ago, two youths from Awarta killed a settler from the nearby illegal settlement of Itemar, and for this act they both received five life sentences. […]

-

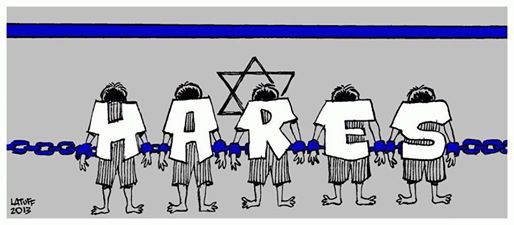

One year on: the Hares Boys

18th March 2014 | The Hares Boys | Occupied Palestine Yesterday the Hares Boys, who are being charged with 20 counts of attempted murder with no evidence whatsoever, have been in an Israeli prison for one year. Now is more important than ever to fully understand the circumstances surrounding the unlawful arrest and imprisonment of Mohammad Suleiman, Ammar […]

Action Alert An Nabi Saleh Apartheid Wall Arrests BDS Bethlehem Bil'in Cast Lead Demonstration Denial of Entry Ethnic Cleansing Farmers Gaza Global Actions Hebron House Demolition International law Israeli Army Jerusalem Live Ammunition Nablus Ni'lin Prisoner Ramallah Rubber-coated steel bullets Settlement Settlers Settler violence Tear-Gas Canister Video