Category: Reports

-

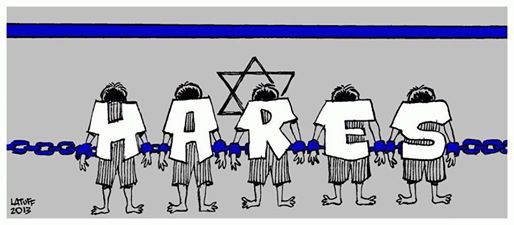

One year on: the Hares Boys

18th March 2014 | The Hares Boys | Occupied Palestine Yesterday the Hares Boys, who are being charged with 20 counts of attempted murder with no evidence whatsoever, have been in an Israeli prison for one year. Now is more important than ever to fully understand the circumstances surrounding the unlawful arrest and imprisonment of Mohammad Suleiman, Ammar…

-

Injustice in Al Maleh

17th March 2014 | International Solidarity Movement, Nablus Team | Jordan Valley, Occupied Palestine The Israeli occupation in Palestine can be seen in many different ways. In the Al Maleh area of the Jordan Valley (area C, which is under full Israeli military control) 450 Palestinian families, including 100 Bedouin families are spread through 13…

-

Remember Rachel

16th March 2014 | International Solidarity Movement | Occupied Palestine On this date 11 years ago, ISM volunteer Rachel Corrie was brutally murdered by the Israeli army in Gaza. Rachel was 23-years-old. This interview was filmed two days before Rachel was killed and her words are still unfortunately relevant when describing the situation in Gaza.…