Category: Reports

-

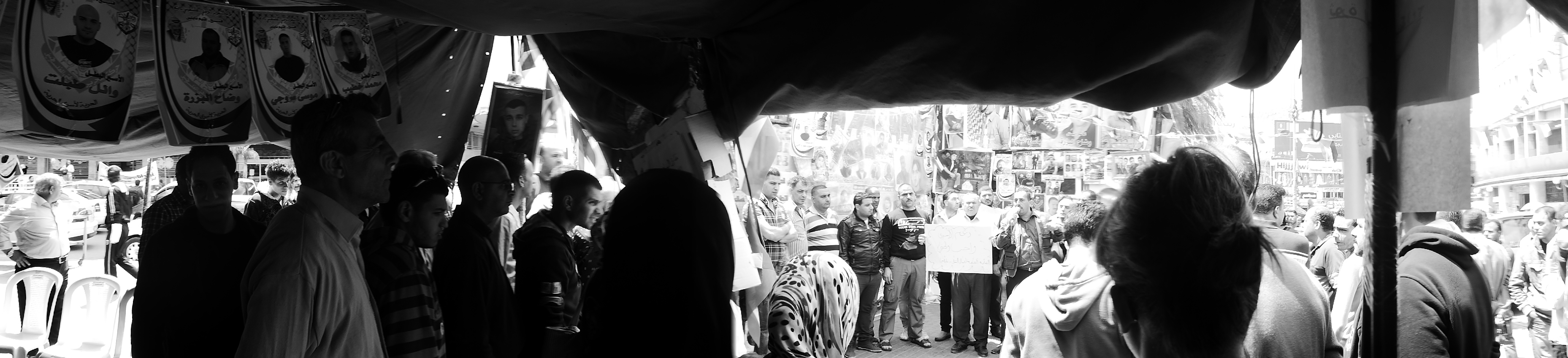

Hunger strike solidarity tent in Nablus

16th May 2014 | International Solidarity Movement, Nablus Team | Nablus, Occupied Palestine Erected in the duar (city center) in the northern Palestinian city of Nablus, is a large tent utilized throughout the day by those in solidarity with the exceeding-one-hundred Palestinian administrative detainees. “We will stay here as long as it takes” says Yousef, a Lawyer and…

-

UPDATED: House demolitions at Khirbet al-Taweel

30th April 2014 | International Solidarity Movement, Nablus Team | Khirbet al-Taweel, Occupied Palestine Update 15th May: On Monday the 12th of May, at 7AM, approximately 350 Israeli soldiers, two buses, and several military jeeps arrived at the remote village of Khirbet al-Taweel and ordered the inhabitants of two houses to remove all furniture in order to proceed with their illegal…

-

14 more arrested as Israeli army intensifies arrest campaign in Kafr Qaddum

13th May 2014 | International Solidarity Movement, Nablus Team | Kafr Qaddum, Occupied Palestine Update 13th May: The eight youths arrested and held following the night raid in Kafr Qaddum have court on the 15th May, at Salem Court, near Jenin. ***** 14 people were arrested in Kafr Qaddum during a night raid on the…