-

Palestinian woman struggles for proper medical treatment

by Wahed Rejol 14 November 2011 | International Solidarity Movement, West Bank In 2004 Amal Jamal was sentenced to 12 years in Israeli prison. A year later the Palestinian woman from Nablus was diagnosed with ovarian cancer. Today from a hospital in Nablus she awaits a decision from Israel authorities that will determine whether she […]

-

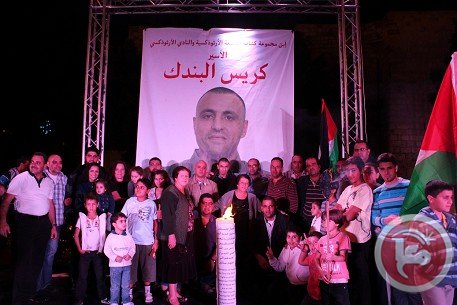

“Only one half of me is free, but the other half is still there, locked up behind Israeli bars”

by Shahd Abusalama 13 November 2011 | Palestine from My Eyes In a nice restaurant overlooking Gaza’s beach, beneath a full moon with a beautiful halo surrounding it, I sat with my new friends who recently were released from Israeli prisons. Their freedom was restricted by Israel’s inhumane rules, including indefinitely deportation from the West […]

-

Girl detained: Israeli military escalates pressure at Hebron checkpoints

by Emma Evertsson 13 November 2011 | International Solidarity Movement, West Bank On November 12 a young teenage girl was being detained at the main checkpoint in Hebron. When internationals were notified she had been detained for more than an hour without any obvious reason. The girl was on her way home with a friend […]

Action Alert An Nabi Saleh Apartheid Wall Arrests BDS Bethlehem Bil'in Cast Lead Demonstration Denial of Entry Ethnic Cleansing Farmers Gaza Global Actions Hebron House Demolition International law Israeli Army Jerusalem Live Ammunition Nablus Ni'lin Prisoner Ramallah Rubber-coated steel bullets Settlement Settlers Settler violence Tear-Gas Canister Video