Category: Journals

-

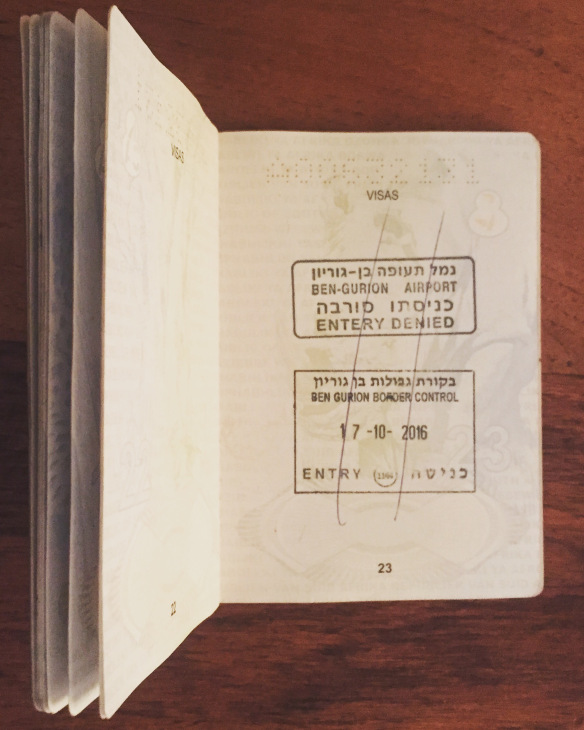

Deported

24th October 2016 | Sarah Robinson | occupied Palestine On Monday, 17 October 2016, I was deported from Israel. This is my story. I left Johannesburg on Sunday evening, 16 October, and flew to Istanbul, Turkey. The check-in process was smooth and I was asked no security related questions. I had a six-hour stopover in…

-

Roadblocks, stun grenades and settler aggression: another Jewish holiday in occupied al-Khalil

23rd October 2016 | International Solidarity Movement, al-Khalil team | Hebron, occupied Palestine The events of Tuesday the 18th of October began to unravel as my friend and I accompanied school children through an Israeli checkpoint (Salaymeh) as they made their way home that afternoon. On our return journey from the school we noticed a…

-

Nowhere to hide: New illegal observation tower in occupied Hebron

3rd October 2016 | International Solidarity Movement, al-Khalil team | Hebron, occupied Palestine Israeli forces put up a CCTV observation tower in the Ibrahimi mosque area, further increasing not only their all-encompassing surveillance of Palestinians, but also their slow but steady illegal annexation of more and more Palestinian land in occupied al-Khalil (Hebron). At the…