Tag: Olive harvest

-

Zaytoun 2025 updates: October 17

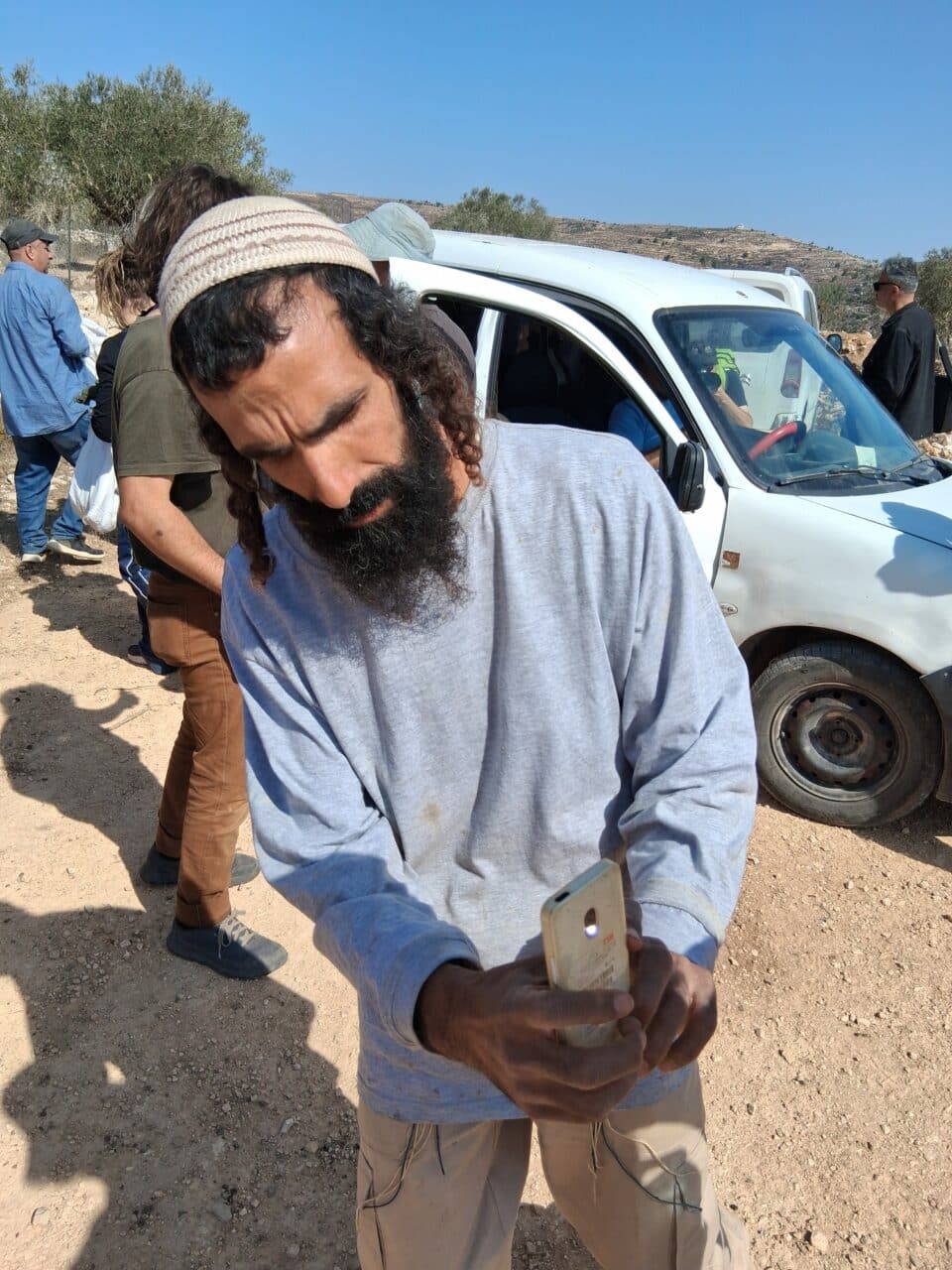

Today’s wrap-up: Ourif/Asira al-Qibliya, South NablusThe security coordinator of the Yitzhar settlement threatened and prevented harvesters from accessing their lands. Qabalan, South-East NablusArmed Israeli colonisers attacked and prevented land owners from reaching their lands in the Abu Sham’on area in the Aqraba valley. Three, including a child were injured and at least 3 cars were…

-

Zaytoun 2025: A “flotilla” to break the siege on Palestine’s olives

Wednesday 15 October, Tulkarm — at around 10.15am large convoy of Palestinian men and women from across the West Bank, together with international activists, arrived in Nazla al-Sharqiya, Tulkarm, to support the Zaytoun 2025 olive harvest campaign. Their destination was a Palestinian olive grove that now has an illegal Israeli outpost right next to it.…

-

Olive Harvest updates: October 13 and 14

October 13 alMughayyer, East RamallahIsraeli citizens cut off some 150 olive trees in the Marj Sia area west of alMughayyer tonight. In recent weeks, the uprooting and cutting off olive trees has happened on a daily basis. Qaryout, South NablusIsraeli citizens set fire in the Batisha area north-west of the village Yanoun, East NablusIsraelis cut…