Tag: Blockade

-

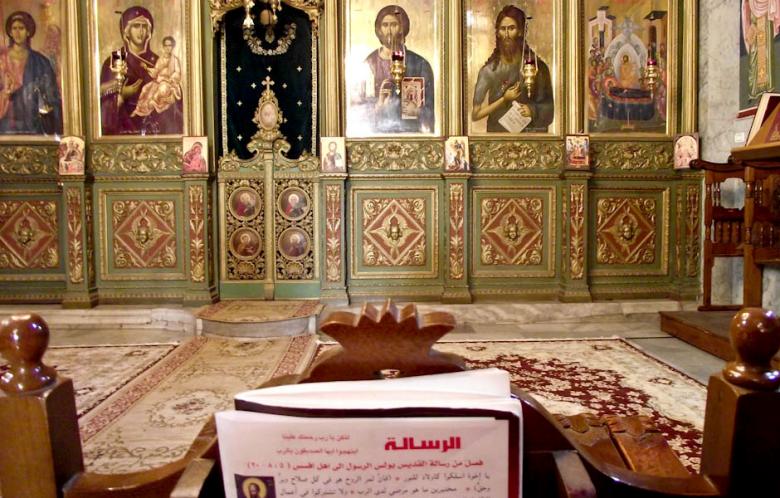

Christmas in Gaza

by Ruqaya Izzidien 24 December 2011 | Al Akhbar English This Christmas marks the third anniversary of the 2008-2009 Israeli war on the Gaza Strip; a winter in which 19-year-old Ramy El Jelda saw his home bombed just two days after Christmas. He returned to the site a couple of days later to find his…

-

Demonstration in the no go zone, Beit Hanoun

by Nathan Stuckey 20 December 2011 Every Tuesday there is a demonstration against the occupation and the Israeli imposed no go zone that surrounds Gaza, stealing much of Gaza’s best farmland. Today, it was unseasonably warm, it felt almost like summer. We started our march from in front of the destroyed buildings Beit Hanoun Agricultural…

-

Israeli navy harasses Palestinian fishermen off Gaza coast

by Rosa Schiano 21 December 2011 | Civil Peace Service Gaza The Oliva sailed from Gaza Seaport at 8:15 am. The Palestinian captain and two international observers from CPS staff were on boardAt 8:45 am Oliva reached four hasakas in the north of the Strip, about 2.2 nautical miles off shore (31° 35.40N / 034°…