Tag: BDS

-

Organisers of Pilsen 2015, don’t host Days of Jerusalem festival

30th April 2015 | International Solidarity Movement – support group | Czech Republic Prominent figures of Czech political and public life call on the organizers of Pilsen 2015 to step down as hosts of the Days of Jerusalem festival. The Days of Jerusalem festival is taking place in the city of Pilsen as part of the European Capital…

-

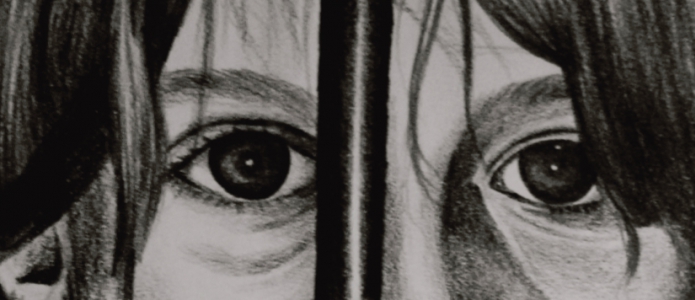

Imprisoned Voices: corporate complicity in the Israeli prison system

20th April 2015 | Corporate Watch | This briefing was published on 17 April 2015 to coincide with the annual day of solidarity with Palestinian prisoners. It collects the memories of the pain, suffering and resilience of Palestinians who have been imprisoned by Israel. In 2013, Corporate Watch visited the West Bank and Gaza Strip and…

-

A call from Gaza: Make Israel Accountable for its Crimes in Gaza – Intensify BDS!

5th September | BDS Movement | Occupied Palestine From the ruins of our towns and cities in Gaza, we send our heartfelt appreciation to all those who stood with us and mobilized during the latest Israeli massacre. In the occupied West Bank, Israel has embarked on one of its largest illegal land grabs in decades…