Category: Journals

-

Sami Janazreh enters 46th day of hunger strike

17th April 2016 | International Solidarity Movement, Al-Khalil Team | Hebron, occupied Palestine Today volunteers from ISM attended a demonstration in Al-Khalil for Prisoners’ Day. Once the main demonstration had ended in the city a group of young Palestinians invited the volunteers to the Fawwar refugee camp outside the city. At the camp they were…

-

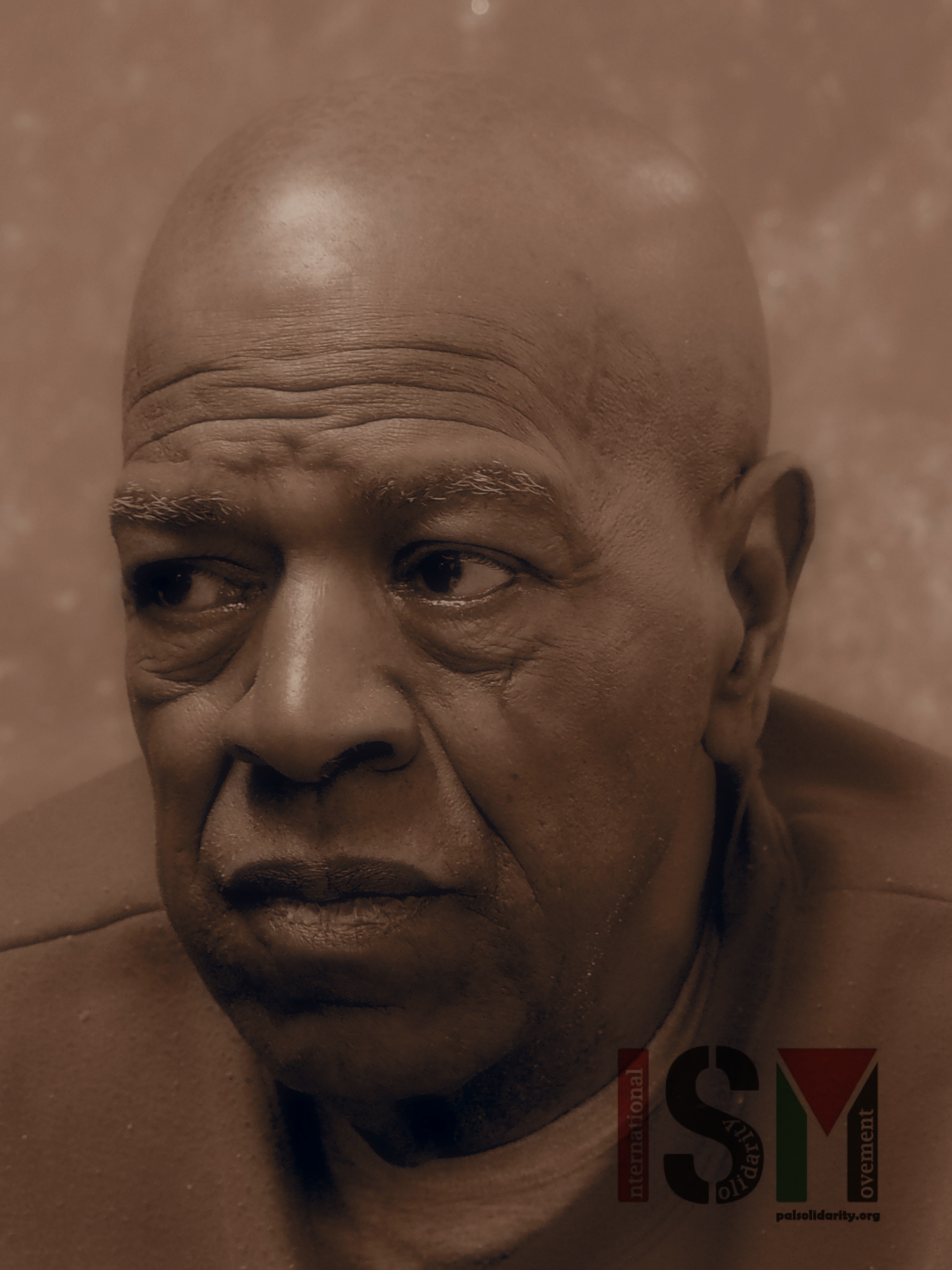

Ali Jiddah – an alternative tour guide

6th April 2016 | International Solidarity Movement, Ramallah Team | Jerusalem, Occupied Palestine Ali greets us international activists with a certain kind of warmth that those who are foreign to the middle east (or Palestine in this case) may have never experienced or have been accustomed to in our home countries. We have all learned very quickly to appreciate the…

-

A night of protective presence needed

3rd April 2016 | International Solidarity Movement, al-Khalil team | al-Khalil, occupied Palestine The two boys met us at the store, shouting the name of our Palestinian contact and waving us along. The cobbled stones in the alley made a nice contrast to the darkness of the night. My feet landed softly on the mud…