18th November 2013 | International Solidarity Movement, Charlie Andreasson | Gaza, Occupied Palestine

An hour before dusk, an armed drones flies low over the rooftops, taking its time, seeking. A few miles away, someone sits, perhaps a young man, perhaps a woman, in front of a screen, secure in a command center. Soon this faceless person will find a target and fire the drone’s deadly cargo.

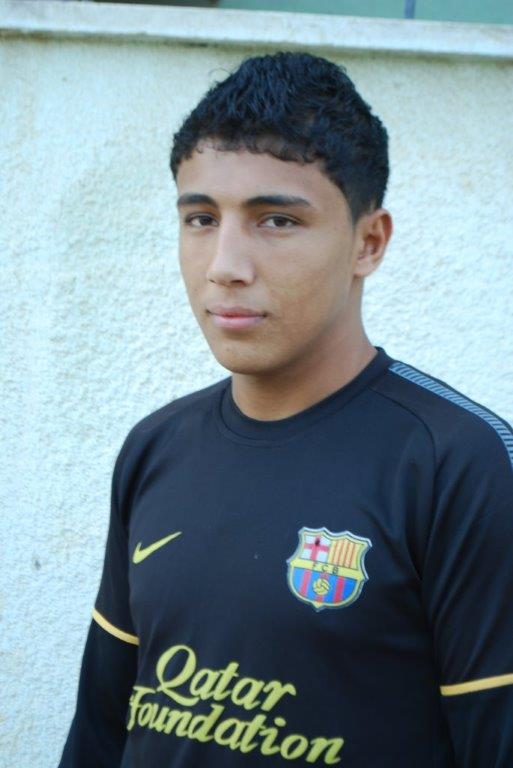

Two boys, cousins, 14 and 15 years old, were playing as boys in that age often do, kicking a ball between them. Adulthood had not yet begun, the future was still made of dreams, and neither was aware of what was just about to befall them.

Meanwhile the man or woman in the command prepared to fly the drone back to its base, make a neat landing, and perhaps get for a pat on the back for a successful mission.

It was 19th August 2011.

Muhamad al-Zaza woke up lying in his own blood next to his cousin Ibrahim al-Zaza. He screamed, but only for a brief moment before he fell into unconsciousness. Muhamad would never hear Ibrahim shout again, nor would they ever kick another ball. Ibrahim died a month later from his injuries, after weeks of struggle against death. Another number for the statistics. Another casualty of the military occupation’s cruelty. A 14-year-old boy who had to atone with his life for the crime of having been born on the wrong side of the separation barrier.

When Muhamad awoke, he lay bandaged at al-Shifa hospital in Gaza, more or less like a mummy. And there could he have died as a direct consequence of the siege. The medical equipment necessary to save the life of someone as badly injured as the two boys was not there. They had to get treatment elsewhere. Still, it took eight days before they were allowed to be transferred to Kaplan hospital, in Israel, the nation behind the attack and which caused their injuries. They were admitted not in recompense, but on a commercial basis, a cynicism that exceeds the limit of the possible.

Ibrahim was immediately placed in an isolated room when he arrived at Kaplan hospital. He had lost a lot of blood and both hands, and most of his internal organs were injured. All efforts to save him were in vain. For Muhamad, the odds were better, but his condition remained critical. Surgeons places eight nails in his leg, and it took several more surgeries to clip muscles and tendons in his legs and hands.

But the hospital was an oasis of humanity for the eleven months he stayed there, very different from what he would encounter during his journeys between hospitals. First he went to Jerusalem; for two months in rehabilitation; then to Nablus, for a month; for back surgery; and then to Egypt. He was refused ambulance transport, and only after a physician at Kaplan hospital, Dr. Tzvia Shapira, paid out of her own pocket could it be arranged. The harassment continued at military checkpoints, with the constant threat soldiers would deny him passage.

When Atef al-Zaza, Muhamad’s father, begins to talk about Dr. Shapira, his eyes glitter like distant stars. She did not let Israeli propaganda and war rhetoric obscure her vision, but saw his son as a human being, and started a fundraising campaign to enable his continued operations and rehabilitation. But despite the warmth that surrounded Muhamad in her care, fear crept in every time he heard the sounds of F-16s from a nearby military airport. He feared not only for his own life, that they would come to finish the job, but also for his family and his friends in Gaza.

I asked him what he experiences today, two years after the attack that could have ended his life, when he hears the sound of the drones as they fly over the rooftops. Muhamad first threw a pleading glance at his father, who said that the nightmares his son once had no longer wake him at night. But when he began to describe the feelings the sound of the drones raise, I saw discomfort reflected in his face, a face whose muscles he struggled to control, and asked another question.

I asked him if he thought that the soldier who controlled the drone experienced it like a computer game, that the people maimed at a safe distance were not of flesh and blood, of emotions and dreams, but just something fictitious on a screen that generates points. This time the answer came immediately, and it was clear he had asked himself the same question. To him it did not matter if the pilot saw it as a computer game or not. “The soldiers, before they sit down in front of the levers, already have dehumanized us Palestinians,” he said. “They do not see us as people. If they did, they could never have done this to us. I would not talk to the soldier if we sat as you and I sit now. Now words can be exchanged between us, not as long as we are not people to them.”

“And,” he says, hesitating a little, “I ‘m afraid that I would hate him, that such a meeting would only produce a worse side of me.”

He pronounces the words with a calm voice, and I try to see the boy as he was before all this happened. The scars he showed me, covering large parts of his body, were obviously not the only ones caused by the drone attack.

The bill for the first eight months of Muhamad’s care in Israel landed on the Palestinian Authority’s desk. A fundraising campaign Dr. Shapira started funded the rest. But more surgery is needed for Muhamad to be able to return to a normal life, something very evident when he showed the injuries on its legs and hand.

During the interview, none of us knew that Dr. Shapira had just launched a new fundraising campaign to at least be able to operate on Muhamed’s hand. When Atef learned this, his eyes again glittered like lightning. But he knows that his son’s story is not unique, that many similar attacks have affected others, and that Dr. Shapira is not enough for everyone.