Tag: Ramallah

-

Internationals harassed and denied entry into Nabi Saleh

by Wahed Rejol 18 November 2011 | International Solidarity Movement, West Bank Following last week’s violence in the village of Nabi Saleh near Ramallah, international observers and activists were today denied entry into the village by Israeli soldiers. The soldiers said that the entire village was a closed military zone and provided paperwork that seemed…

-

In Ramallah Palestine tastes freedom at release of prisoners

18 October 2011 | International Solidarity Movement, West Bank It was the third time that Omar, 21, tried to write his name and cell number on a piece of paper in vain. His hands were shaking and the fingers, pale as the face, could barely hold the pen. On the fifth try he was able to write…

-

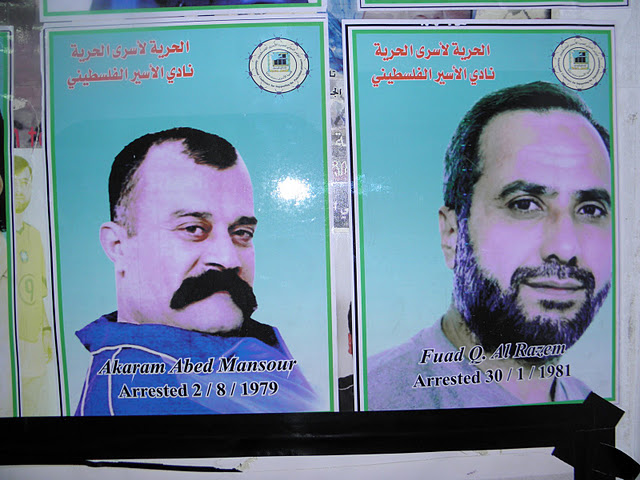

In Photos: Palestinians unite to support prisoner hunger strike

12 October 2011 | International Solidarity Movement, West Bank and Gaza On Tuesday the 27th of September, an open-ended hunger strike was initiated until the fulfillment of 9 demands by Palestinian prisoners, which include the right to family visits, end to the use of isolation as a punishment against detainees, and profiteering of Israeli prisons from…