Tag: International law

-

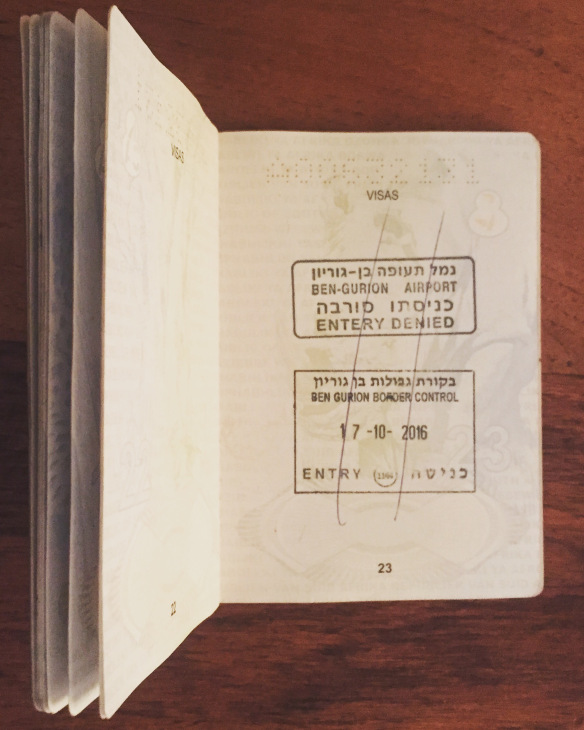

Deported

24th October 2016 | Sarah Robinson | occupied Palestine On Monday, 17 October 2016, I was deported from Israel. This is my story. I left Johannesburg on Sunday evening, 16 October, and flew to Istanbul, Turkey. The check-in process was smooth and I was asked no security related questions. I had a six-hour stopover in…

-

‘We are strong and we will be free’ – Hashem Azzeh memorial

24th October 2016 | International Solidarity Movement, al-Khalil team | Hebron, occupied Palestine One year has lapsed since the passing of Hashem Azzeh, a devoted husband and loving father of three, and close friend of ISM. Hashem died following an exacerbation of a latent heart condition that was triggered by tear gas inhalation suffered in…

-

Israeli Forces Shoot a Palestinian Fisherman for the Third Time

24th October 2016 | International Solidarity Movement, Gaza-team | Gaza, occupied Palestine On Sep 5th, 2016, the Gaza fisherman, Ahmed Mohamed Zaied. 32 years of age, was fishing along with his friend using a hasaka (small boat). They were fishing closer than 1.5 miles in the Palestinian territorial waters, in the northern part of the…