21st October 2013 | International Solidarity Movement, Charlie Andreasson | Gaza, Occupied Palestine

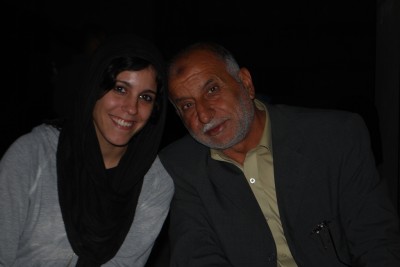

An older man meets us when we step out of the taxi, a patriarch, his back straight, with a firm handshake and a welcoming smile. The other activists I shared a taxi with have all been there before, and we sit with no major ceremonies at the gate of the house as the sun casts its last warm rays upon us.

Soon we are served soft drinks and biscuits, followed by coffee, tea and dates. Our visit is clearly expected. Around us gather children and grandchildren.

By Palestinian standards, Abu Jamal Abu Taima is a large-scale farmer with his 50 dunams. But he also has many mouths to feed: three generations with 71 people. “It was crowded during Eid,” he says with a smile that shows more pride than concern with making room for everyone. But as we begin to discuss the conditions of this great crowd, the smile vanishes.

The years between 1995 and 2001 were something of a golden age. He grew a variety of products, and had greenhouses and a substantial income from what he could export. Then the worries began. His land is adjacent to the Israeli separation barrier, and as Israeli forces expanded the “buffer zone,” it swallowed more and more of his land beside it.

Within this zone, there are no longer any olive or other fruit trees. In 2003 Israeli bulldozers devastated his greenhouse and former home. All he can grow there now is wheat, because it does not need to be tended as regularly as other crops.

And it is only wheat that he hopes to sow when the rains start in November. The occupying power does not allow irrigation. They destroy any irrigation pipes in the area. There is also the danger of death if farmers go onto their fields to manage crops.

Today Abu Taima can grow enough to feed his family, but no more. Before his olive trees in the “buffer zone” were destroyed, they produced enough olives for 70 bottles of olive oil. Those left this year gave six. No exports of what he can grow are allowed.

Farmers grow much less with their greenhouses gone, and they are not given access to their fields to use artificial fertilizers or irrigation.

There are fuel shortages. When given the opportunity to obtain fuel, the price has nearly doubled. Some goods, like dates, are cheaper, precisely because they can no longer be exported. Other crops, costlier to produce, will be more expensive for buyers.

Since they discovered the tunnel between the Gaza Strip and Israel, Israeli forces had become more aggressive. Only a few days ago, a shepherd was shot at, even though it was obvious what he was doing. We understand Abu Taima’s hope that we and other activists in Gaza will put our solidarity into action. This season, we will join the planting and harvesting in yellow vests.

But a question grows stronger within me, and I finally have to ask it. “Since the situation only seems to get worse, would you then want your sons to one day take over from you?” I have to ask it twice, rephrasing it slightly, when he does not seem to understand what I mean.

“Palestinians do not leave their land easily,” he explains patiently. “It gives life. I have no desire to be at a center of political and strategic interests. I just ended up there. All I want is to cultivate my land and support myself and my family.

“And if we leave the land, what happens then? Will Israel advance their positions, crowding us further? It may be another Nakba. I have a responsibility not only to my family but also to Palestine.”