by Aaron

21 February 2012 | International Solidarity Movement, West Bank

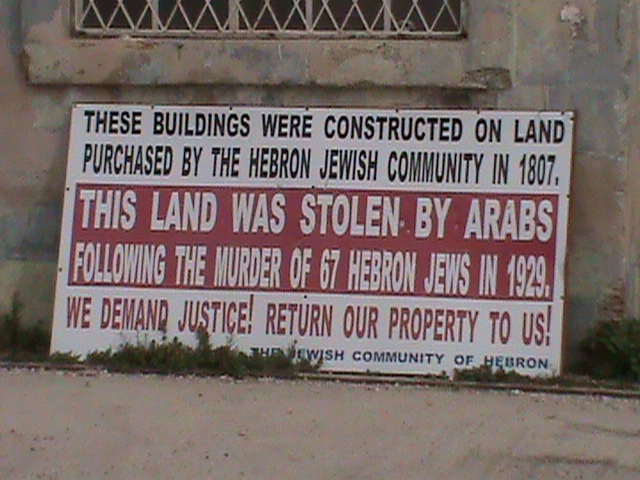

If you ask an Israeli settler in or around Al-Khalil (Hebron) what calls them to live on contested land, most will speak to a religious connection to the city and the Cave of the Machpelach (“patriarchs”), where Jews, Muslims, and Christians come to revere the biblical figures believed to be buried there. A series of signs posted nearby along Shuhada Street, the once-main road and market district now closed to Palestinians, tell a story of Hebronite Jewish habitation dating from biblical times, brought to a sharp and bloody end with a 1929 pogrom, which resulted in the deaths of 67 Jewish residents and the displacement of the survivors. Citing this narrative, many of today’s settlers justify their occupation of the old city as a rebirth and continuation of this community, a story echoed in publications distributed by the Gutnick Center (a Jewish cultural center) and soldier-escorted weekly tours through the Palestinian market. The problem with this narrative is that no one, not even the survivors’ descendants, agrees on it.

On Monday, February 20th, the Jerusalem Post published an article presenting the conflict between the survivors’ descendants as a microcosm for Jewish public opinion, some of whom support the settlements and a growing number who oppose Hebron’s especially active settler community, one which Yair Keidan calls “a loaded bomb that can blow up peace altogether.” Both sides have signed petitions to the Israeli government, asking variously to maintain, evacuate, and/or halt settlement activity, and both groups claim a right to the legacy of their parent community.

“You can’t bring back the dead,” said Ya’acov Castel, a survivor from 1929, “but there are people living here now who are carrying out the dream of the Jews who lived here for hundreds of years.” Yona Rochlin, whose family went back many generations in pre-1929 Hebron, argues the opposite—pointing out that the majority of settlers are US immigrants, who have settled in a foreign city unfamiliar with the customs, language, or neighborly habits of the people they claim as spiritual forebearers. Unlike the predominantly Sephardi and Mizrahi (Spanish/North African and Middle Eastern respectively) Jewish minority that coexisted with a Muslim majority for five centuries, she says that today’s settlers “came to the city to take revenge for the 1929 massacre and their main idea was to drive out the Arabs and turn Hebron into a Jewish city.”

Hebronite settlers have many claims to fame, including the first West Bank settlement Kiryat Arba (founded 1968, pop. 7200) and the only settlements within the bounds of a Palestinian city—Avraham Avinu, Beit Hadassah, and Beit Romano, which lie at the heart of the Old City and fall under Israeli military control. They are also known to be among the most violent and hardliner, with many claiming allegiance to the Kahanist, Gush Emunim, and other extremist Jewish political and religious sects. Particularly infamous Kahanists include Baruch Marzel, founder of the Jewish National Front, and Baruch Goldstein, who in 1994 massacred 29 and injured over 150 Muslims at prayer in the Mosque al-Ibrahimi. Today Goldstein, who was killed during the attack, is venerated as a hero and martyr—and his tomb in Kiryat Arba continues to draw extremist pilgrims, even though his shrine was removed in 1999.

Rochlin, a politically active parent and child of conservative Jewish parents, in 1996 coauthored an open letter to the Israeli government, “Message from the original Jewish community of Hebron: Evacuate settlers,” which stated, “[Hebronite settlers] are alien to the culture and way of life of the Hebron Jews, who in the course of generations created a heritage of peace between peoples and understanding between faiths.” She sees evidence of this tradition in the fact that Muslim neighbors intervened to save her family and over 400 more when the Jewish community was attacked in 1929. Who exactly did the killing, and from where, is uncertain—but there is surprisingly little disagreement over the 19+ Palestinian families that sheltered and defended Jews. Although some Palestinian community members invited their neighbors to stay or return, by 1936 the British Mandate had relocated the remaining Jews to Jerusalem, Tel Aviv and elsewhere.

Curiously, although the Israeli Jews’ narratives tell radically different stories, many area Palestinians also know a great deal about the pogrom and mourn the loss of friends and neighbors. For Muhammad, head of the Abu Aisha family who live in the famed ‘caged house’ on Tel Rumeida, where their home is surrounded by settlement homes, it is a matter of family pride that his father is named among the Palestinians to save Jewish residents. Nonetheless, the Abu Aisha family struggles with daily harassment at the hands of settlers, who occupy land all around the home. Hajj Yussef, one of the few surviving Palestinians who responded in 1929, talks about “our Palestinian Jews,” who dressed and spoke like non-Jewish neighbors. To Yussef, like the children of his refugee neighbors, the obstacle to peace in Hebron lies not in difference but attitude and actions: “I have no problem living with the Jews, like we lived many years ago. But today’s settlers are not Palestinian Jews, they came here from abroad. And I have a problem if the Jews live in my country as occupiers and settlers.”

Open Shuhada Street, the international campaign to end Israeli Apartheid in Al-Khalil/Hebron will continue February 20th through 25th, with actions and cultural events in Khalil and around the world. Each day, we will cover a different aspect of the Occupation’s effects on Shuhada Street and the city generally.

Continue to follow www.palsolidarity.org throughout the week for more stories and analysis.

Aaron is a volunteer with International Solidarity Movement (name has been changed).