by Victoria Macchi, Skin Magazine

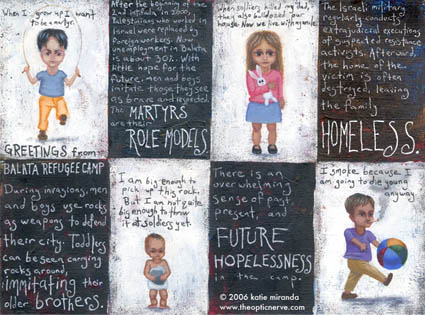

Katie Miranda’s “postcards” create visual dispatches to the American people of life, death, and innocence demolished in Palestine

Two young men, backs turned, wrists bound, heads hanging – paired with anger, a mouth stretched wide open in rage and spewing hate. “You are disgusting Arabs and you should be beaten like animals and stay in jail”.

You don’t look at Katie Miranda’s work. You feel it, a punch in the gut that sucks the wind out, replaces it with incredulity, then knocks you down again as you struggle to get up. Yet her pieces, reflections of life in occupied Palestine, are anything but hyperbolic. Both an artist living

in the West Bank city of Hebron and a volunteer in the International Solidarity Movement (ISM), Katie Miranda has walked the streets of the West Bank alongside Palestinians, drank the same water, protected their children, broken bread with their families – and her paintings reflect it. Her “Postcards from Palestine” series is an eternal testimony to a wounded people. The ongoing collection of paintings of people she has met comes with a message to the American people, exactly like a postcard – although instead of margaritas, sunsets and dolphins, the paintings reflect the violence committed against Palestinians by the IOF and settlers in the territories.

“I wanted to use my artistic ability to tell the story about what’s happening here,” says Katie, a 31-year-old San Francisco native. “I’m an illustrator by trade, so creating pictures that tell a story is what I was trained in… I just decided to interview people about their life and paint about individuals and about situations I witnessed.” As a human rights worker in the West Bank, she has a deep reservoir of stories; most burst with acts of hatred, moments of irony, wisps of humour. “A good deal of the violence is perpetuated by children because of an Israeli law that allows them to be free from arrest and prosecution if they are under the age of 12,” explains Katie.

In one postcard, the innocence of children is portrayed in the hopeless eyes of a girl holding a stuffed rabbit, her father killed by IOF soldiers and her house demolished, which are juxtaposed with a carefree boy playing with a ball, a cigarette dangling from his mouth. It’s difficult to imagine humans so jaded so young. But again, they have never known an unoccupied Palestine, freedom of movement, or simple justice for their friends and family slain during four decades of war.

Katie recalls an incident when life and art collided. It was the day after she arrived in Palestine, back in May. The ISM was called to the Balata refugee camp because the IOF had invaded and, the reports said, were killing people randomly. “ISM helps with medical evacuations in these situations,” Katie explains. “Sometimes when a person is shot or injured, the soldiers refuse to let the ambulance leave, so we try to negotiate with them to allow the ambulance pass. Right before we got there these two kids were killed.” Best friends Ibrahim Issa and Mohammad Natoor, both 17, were drinking tea on the roof of their apartment when they were shot by a sniper. Katie documented their funeral in one of her postcards, and in her message to the American people noted what they loved and how they smiled – and just how young they were. She transcribed the words of Ibrahim’s brother:

“Anywhere you see him, you will see Mohammad Natoor with him and anywhere you see Ibrahim and Mohammad, you will see them smile at you and say ‘hello, how can we help you?’” Mohammad was killed by Israeli forces on his 17th birthday.

The pair are immortalised on one of Katie’s postcards. “It was such an emotional experience because they were just kids, you know, they hadn’t done anything wrong,” says the artist. “And no one will be held responsible. It was a meaningless death. I couldn’t get the image of those kids’ faces out of my head for weeks. So I dealt with that and the trauma of being in a place under siege by painting the picture of Ibrahim during his funeral procession that wouldn’t leave my head.” She later painted a picture of him from a photo studio portrait. “When I gave it to the family it was really emotional. I could tell they were really touched and really liked it – but of course it also reminded them that their son or brother was dead. It was hard for me to look at his brother’s face when I gave him the portrait.”

In another postcard, a fairly innocuous image, a young boy is shown with his mouth gaping open and a few teeth missing. But it is rendered appalling by the explanation – a settler woman had filled his mouth with rocks and slammed his jaw shut, shattering his teeth. Another postcard elevates a Palestinian man, now paraplegic after a shot to the neck by an Israeli sniper in 2000, by painting him at a sharp angle, facing upwards, with the colours of the Palestinian flag bursting behind his head. Katie hopes this empowers the wheelchair-bound former karate champion.

The “Postcards”, though, are only her latest artistic project in Palestine. Katie, who estimates she has been attacked by settlers and soldiers around 50 times since arriving to Hebron in May, originally wanted to paint over the settlers’ anti-Arab graffiti. In one case, she covered up the words “Die Arab sand-niggers” with a mural of children playing in the sun. “When I first saw that graffiti it really disgusted me,” she says. “I wanted to get rid of it and I thought a nice cheerful mural of kids playing would be a good solution. It’s the idea of fighting hate with love.” “The mural is still there, but it has been defaced by the settlers, which I knew would happen. But it doesn’t really bother me because I was expecting it and it’s just another example of how hateful these people are.” She also wanted to obscure another spray-painted slogan, spread over two metal doors, that read “Gas the Arabs.” The Palestinian residents opposed the idea, explaining that the racist graffiti should stay precisely because it is so shocking. “When tourists, journalists and NGOs come into the area they are so shocked and horrified that they write and talk about it,” says Katie. “It’s also a great opportunity to see visual evidence of the disgusting nature of these people who live [in the settlements].”

While in Palestine, Katie also painted on what is becoming the largest canvas in the world – the West Bank wall. Her politically relevant reinterpretation of Michelangelo’s Pieta remains on the grey concrete near the Qalandia checkpoint. Eyes shut, palm upturned – in resignation, desperation – a woman holds a dead husband/brother/father/son who is slumped on her lap. “When I got the idea [in 2004], I knew that it had to be painted on the apartheid wall,” she says. “But I never imagined I’d actually be able to get it together to go to Palestine and do it.” She also painted a Soviet-esque angular figure of a man in black and white swinging a sledge-hammer into the wall – denting it but not yet breaking it down. “I hope [the murals] are destroyed when the wall comes down, inshallah,” says Katie. Her creativity enhances her non-violent resistance to the Israeli occupation. Along with an ISM colleague, Katie performed “fire circuses” in Hebron. “No one had ever seen anything like it before and it was a big hit, especially the kids… We’d start performing when we’d see soldiers detaining and harassing Palestinians. It’s just such an absurd situation to see a bunch of teenage punks with guns start acting disrespectfully and physically aggressive towards women and old men for no reason at all. We dealt with that absurdity by adding to it… it had the effect of drawing the soldier’s attention away from the Palestinians and also entertaining the Palestinians while they were being detained.”

One of the greatest challenges of living in Palestine, says Katie, is having to accepting that my tax dollars as an American go towards funding the Occupation and the violence. “Americans grow up learning the values that everyone is equal and everyone, in theory, has the same rights. “To see that this is neither true in theory nor in practice in Palestine turned my world upside down – it’s like all of a sudden someone tells you 1 + 1 = 3 and you just have to accept it.” As Katie asks in her blog, also entitled Postcards from Palestine “Is this apartheid yet?”

More of Katie’s artwork can be seen on her website: www.theopticnerve.com

She also maintains a blog at: moomin13.livejournal.com

Occupation Hazards

Katie shares with Skin her top altercations with the IDF:

1. Water supplies being poisoned by Israeli soldiers

Our water is kept in tanks on the roof of our apartment building. The IDF soldiers occasionally use our roof as one of their outposts. One day we discovered some creepy-crawly things in the water coming out of the kitchen sink faucet. We went up on the roof to investigate and discovered that our water tanks had been turned into an IDF garbage dump. The garbage included forks, spoons, knives, army netting, unexploded bullets, paper, plastic, glass, bricks, broken pipes, pudding containers, an extremely outdated, unopened yoghurt package, and plastic trays on which soldiers’ meals are served. The water on the bottom of the tank was completely black but the water on the top was clear. When I smelled it I felt like I was going to throw up. Since we get the water on the top of the tank first, we didn’t notice a problem until we noticed wriggly things in our water. After we made the discovery I went to the doctor who found that I had some kind of gnarly amoebas living in my stomach. One volunteer was diagnosed with tapeworm.

2. Being trampled by a police horse

There were some Israeli mounted police who were allowing the horses to s**t all over this area in Jerusalem where Palestinians frequently pray… I went up to one of them, asked them if they had any intention of cleaning up after their horses and the cop jerked the reins of the horse so the horse’s head knocked my head and then the cop ran the horse into me, causing me to fall over. I wound up under the horse that then trampled on my foot. When my friend came to my assistance and started screaming at the cops, he was beaten. We were really lucky in that neither of us were hurt badly.

3. False accusations of assault on a settler

I was taken to the Israeli Hebron police station on suspicion of assault after a settler accused me of scratching her as I escorted a woman past a group of settlers who had been taunting, harassing and throwing rocks at Palestinians. The Israeli police present did nothing to rein in the settlers and did not see me assault anyone because of course I didn’t. But nevertheless I was taken into custody and interrogated.