Tag: Settlers

-

Palestinians hospitalised in settler attack near Ramallah

15 October, 2023 | International Solidarity Movement | Wadi Siq Armed settlers attacked Palestinians and international volunteers in the Bedouin village of Wadi Siq, east of Ramallah, on Thursday (October 12) hospitalising two people. Villagers were also beaten after the illegal settlers returned for a second attack later that day, ISMers were told. …

-

Attacks and disruption in Al-Khalil as settlers celebrate Sarah’s Day

December 29 | International Solidarity Movement | Al-Khalil Around 30,000 settlers gathered in Al- Khalil (Hebron) on Saturday, November 19, to celebrate Sarah’s Sabbath and wreaked havoc in the Old City market, attacking Palestinians and their shops, houses and destroying cars. This happened under the watch of the Israeli army who cordoned the area so…

-

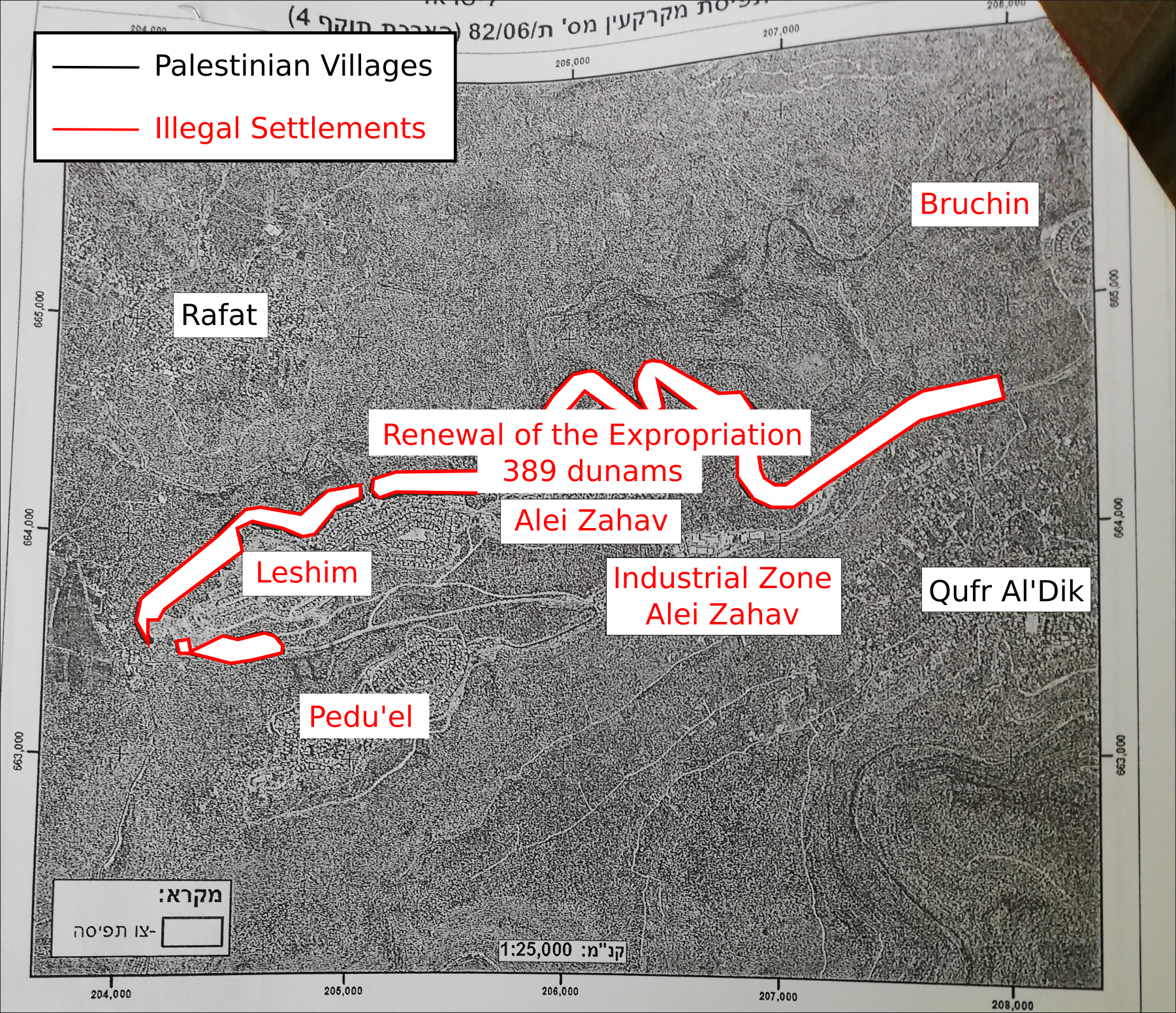

Report on Land Confiscations by the Israeli Army in Salfeet and Qalqilya Area

The Israeli Occupation Forces have recently announced a new series of land seizures in eleven villages in Salfeet and Qalqilya, Occupied Palestine, a move that will affect almost 1 million square metres of Palestinian land.