Tag: Prisoner

-

Israeli forces escalate restrictions and violence against Palestinians during Sukkot-holiday

2nd October 2015 | International Solidarity Movement, Al-Khalil team | Hebron, occupied Palestine Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday, the 28th – 30th September 2015 is the Jewish holiday of Sukkot. In the occupied West Bank city of al-Khalil (Hebron), while Israeli settlers from the many illegal settlements within al-Khalil celebrate their holiday, Israeli forces have escalated…

-

Double standards, one rule for all – except Palestinians

27th September 2015 | International Solidarity Movement, Al-Khalil team | Nabi Saleh, occupied Palestine On the 28th of August, Mahmoud Tamimi was arrested in Nabi Saleh during the weekly non violent demonstration. Every Friday, just after the prayer, the residents demonstrate against the expansion of the illegal settlement of Halamish which has continuously confiscated Palestinian…

-

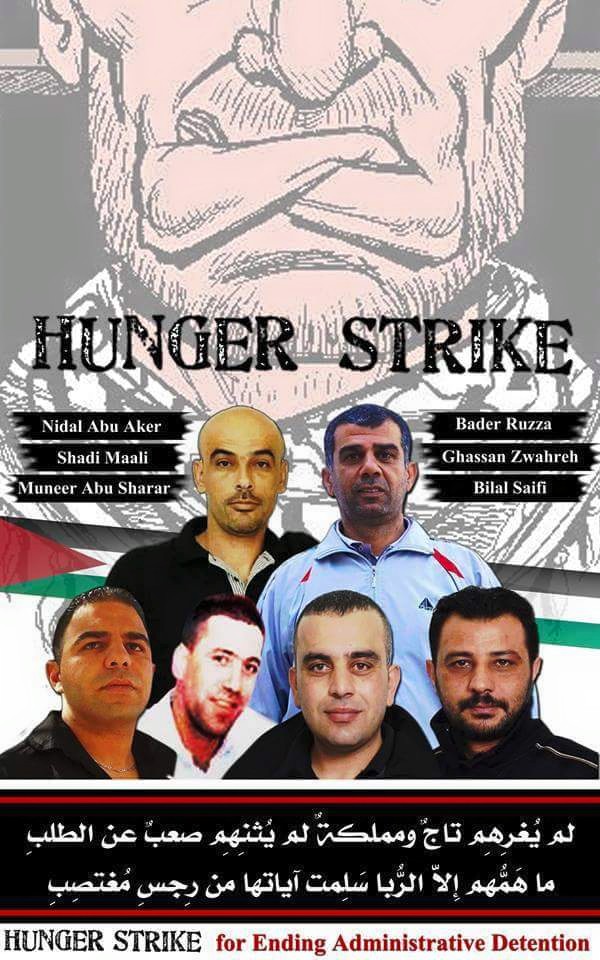

ACTION ALERT! Battle of breaking the chains: 25 days of hunger strike for Palestinian prisoners

15th September | Palestinian Prisoner Solidarity Network | Occupied Palestine Palestinian prisoners in Israeli administrative detention are continuing their hunger strike to demand an end to imprisonment without charge or trial. Nidal Abu Aker, Ghassan Zawahreh, Shadi Ma’ali, Munir Abu Sharar,Badr al-Ruzza, Bilal Daoud Saifi and Suleiman Eskafi are all isolated by the Israeli prison…