Tag: Drone

-

Gaza: Life beneath the drones

25th January 2014 | Corporate Watch, Tom Anderson and Therezia Cooper | Gaza, Occupied Palestine In the Gaza Strip there is no escape from Israel’s drones. Nicknameed ‘zenana’by Palestinians because of their noisy buzzing, the drones (remote control aircraft) are omnipresent. Sometimes they are there to carry out an extra judicial killing and sometimes they are there…

-

Forging new links to boycott movement in Gaza

16th December 2013 | The Electronic Intifada, Joe Catron | Gaza City, Occupied Palestine The Gaza Strip, now in its seventh year of a comprehensive siege by Israel, has faced increased hardships since the 3 July coup in neighboring Egypt. On 26 November, the United Nations’ Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs warned that the Palestinian enclave…

-

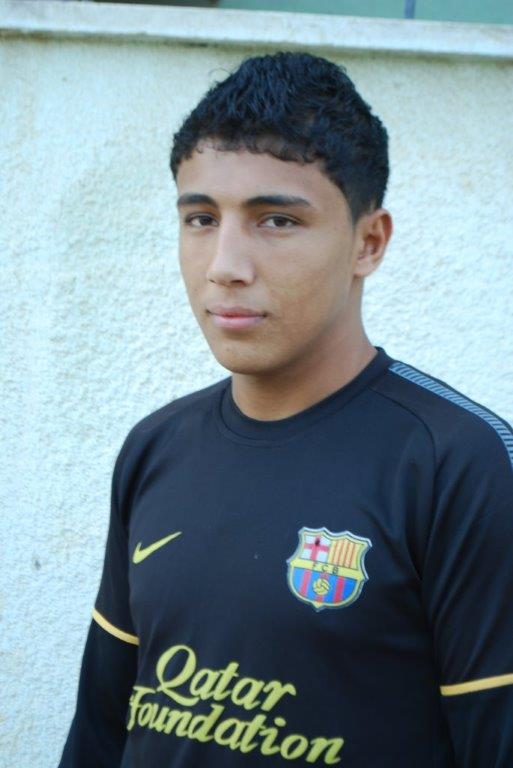

Gaza boy remembers Israeli drone strike that maimed him and killed his cousin

18th November 2013 | International Solidarity Movement, Charlie Andreasson | Gaza, Occupied Palestine An hour before dusk, an armed drones flies low over the rooftops, taking its time, seeking. A few miles away, someone sits, perhaps a young man, perhaps a woman, in front of a screen, secure in a command center. Soon this faceless person…