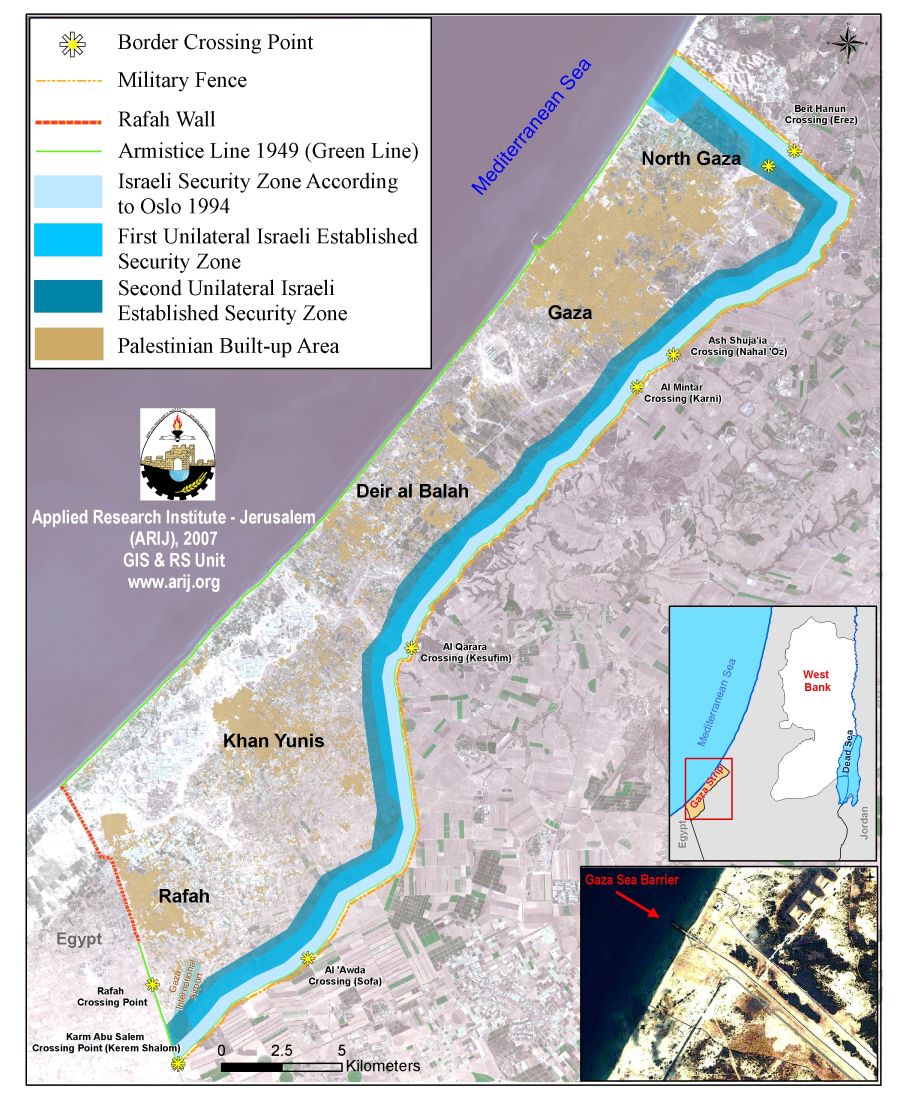

Tag: Buffer Zone

-

Music against the No Go Zone

by Rosa Schiano 31 January 2012 | il Blog di Oliva Every Tuesday we demonstrate at the Erez border crossing, in Beit Hanoun, in the northern Gaza Strip. The demonstration started at about 11:00 AM. We headed for the No Go Zone. The No Go Zone is an area taken by Israel that extends along Gaza’s entire…

-

Beit Hanoun demonstration under fire

by Nathan Stuckey 25 January 2012 | International Solidarity Movement, Gaza Strip Gaza was treated to a strange new sight today, not really new, but something that has not been seen in Gaza in a long time: tear gas. In Gaza protests are not smashed with tear gas and clubs like in the West Bank,…

-

Live ammunition fired at peaceful demonstrators in Gaza No Go Zone

24 January 2012 | International Solidarity Movement In a peaceful demonstration into the Gaza no go zone that began around 10:30am today, January 24 2012, demonstrators report that at least 50 rounds of live ammunition were fired directly at Palestinian and international solidarity activists. Contact: Nathan Stuckey, International Solidarity Movement activist Phone Number: 00970597650864 Email: GazaISM@gmail.com …