Category: Photo Story

-

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Israel displaces last two families from Al Khalayel valley, Al Mughayyir

A violent campaign aimed at forcibly displacing Palestinian families from the Al Khalayel valley south of Al Mughayyir (occupied West Bank) has achieved its goal. Two years of coordinated attacks between illegal settlers and Israeli occupation forces finally pushed out the last two remaining families: Abu Najeh and Abu Naim/Abu Hamam. The Abu Najeh family compound comprised…

-

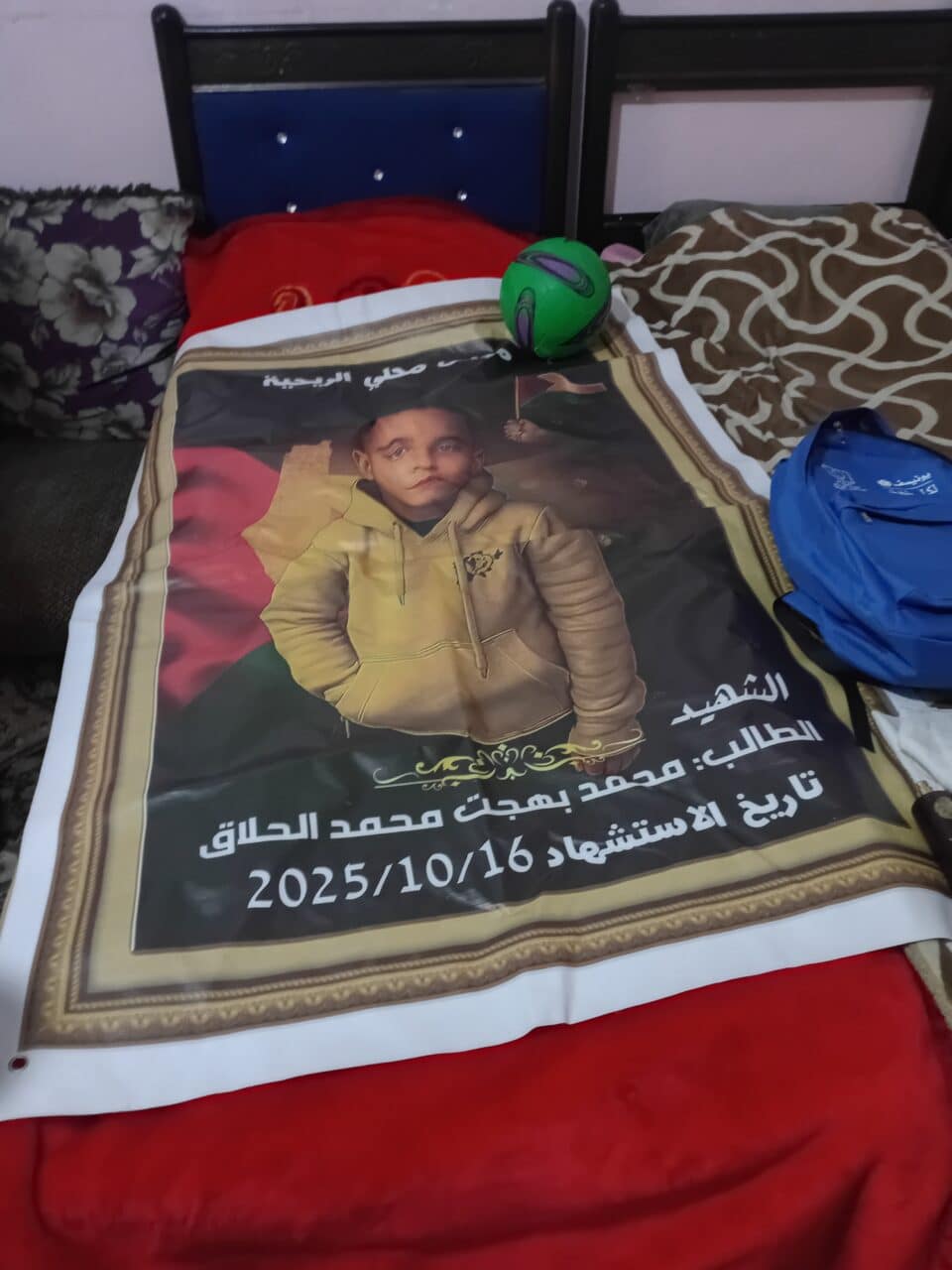

Israel’s War on Children

On the evening of Thursday, October 16, we got word that Israel Occupation Forces (IOF) shot in the abdomen a nine-year-old boy in al-Rihiya. A small village close to Al Fawwar refugee camp, al-Rihiya is 4 miles outside of Al Khalil (Hebron). It was established in 1951 on 1 square km of land to house…

-

Forced Eviction at Gunpoint in Tulkarem

By Diana Khwaelid | Tulkarem – West Bank | October 2, 2025 It is evidently not enough for Israel to “only” deport more than 90% of the residents of the Tulkarem refugee camp in the northern West Bank. The deportations are happening now, coinciding with the launch of a massive military operation on the North…