Category: Journals

-

Freedom Riders: I witnessed six Palestinian activists demand freedom

by Holly 16 November 2011 | Carbonating Change Yesterday I witnessed six Palestinian activists demand freedom, justice and dignity as they defied Israel’s apartheid policies when the group successfully boarded settler-only buses and attempted to enter East Jerusalem, where they were eventually brutally dragged off and arrested by the Israeli Occupying Forces (IOF). At the press…

-

Meanwhile in Gaza

by Radhika S. 15 November 2011 | Notes from Behind the Blockade I awoke today with the news that the NYPD was clearing out Occupy Wall Street and that Israeli tanks were shelling “northern Gaza.” In the West Bank, Palestinian Freedom Riders, inspired by the US freedom riders of the 1960s, were getting ready to board segregated…

-

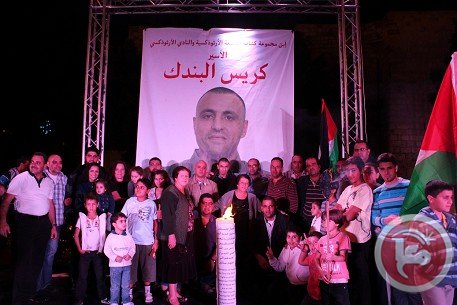

“Only one half of me is free, but the other half is still there, locked up behind Israeli bars”

by Shahd Abusalama 13 November 2011 | Palestine from My Eyes In a nice restaurant overlooking Gaza’s beach, beneath a full moon with a beautiful halo surrounding it, I sat with my new friends who recently were released from Israeli prisons. Their freedom was restricted by Israel’s inhumane rules, including indefinitely deportation from the West…