Category: Features

-

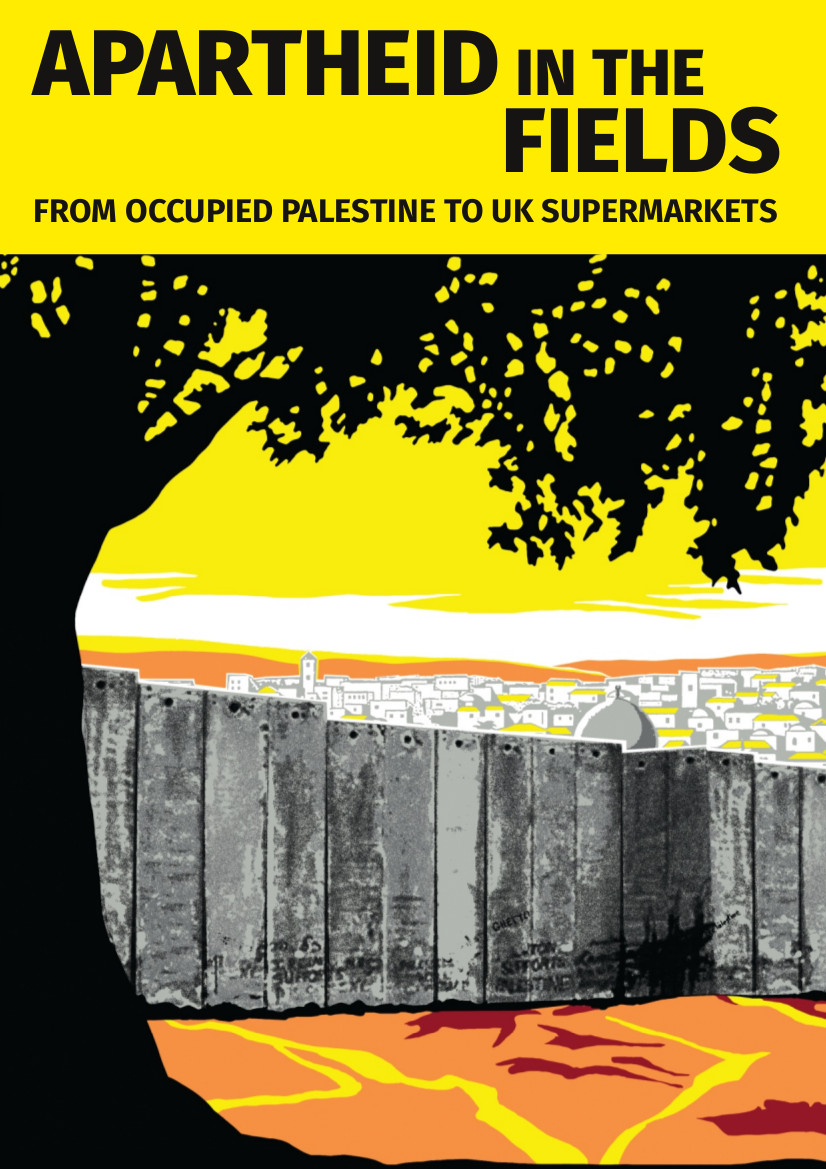

Apartheid in the fields: Part 1 Gaza: farming under siege

29th March 2016 | International Solidarity Movement, al-Khalil team | Gaza Strip, occupied Palestine A new report from Corporate Watch outlines exactly how the food grown in the illegal settlements of Palestine gets to our plates in Britain, and what we (in Britain) can do about it. The situations in Gaza and the West Bank…

-

Israeli forces return to dehumanizing number system in wake of Hebron killings

26th March 2016 | International Solidarity Movement, al-Khalil team | Hebron, West Bank, occupied Palestine After completely closing Shuhada checkpoint to Palestinians in occupied al-Khalil (Hebron) on Thursday, 24th March 2016, Israeli forces have now returned to the practice of ‘numbering’ Palestinian residents in order to restrict access to the adjacent neighborhoods. Soldiers are now…

-

New stun grenades used at Ofer military prison demonstration

26th March 2016 | International Solidarity Movement, al-Khalil team | Ofer, occupied West Bank On 25th March 2016, Israeli forces at Ofer military prison injured 8 Palestinians with various kinds of weapons, and later on attacked the nearby village of Beitunia, injuring even more. A demonstration against the Israeli military occupation and for the freedom…