by: Yifat Appelbaum

Firas used to live in the old city of Hebron until 1 year ago when he and his whole family left as a result of the settler and soldier violence.

He asked me to go with him to visit the old house, which his family still owns. He wanted to see what kind of condition it was in and he knew the soldiers at the checkpoint below the building and the Israeli settlers in this formerly Palestinian neighborhood would make problems for him if he went alone.

We attempted to take the short route down Shuhada Street which would have put us at Firas’s house in about 5 minutes. Shuhada Street has been closed to Palestinians for the past 6 years. However, in 2007 the Military Legal Advisor of the IDF declared in response to a letter from the Association of Civil Rights in Israel (ACRI) that this order was invalid. Captain Harel Weinberg, Advisor in the Criminal and Security Department of the IDF stated in a letter to ACRI “With regard to this issue we would like to inform you that as a result of an inquiry that was carried out by Judea Brigade it appears that you are correct, and in fact Palestinians have been erroneously denied pedestrian movement through Shuhada Street, west of Gross Square. A new instruction has therefore been issued by officials from the IDF Division that permits pedestrian movement, which will of course be subject to security checks. We hope that this will be sufficient to resolve the issue denoted above.”

Despite his declaration, Palestinians are still not allowed to walk on this street. No one knows why but I suspect it has something to do with the settlers giving orders to the soldiers instead of the commanders giving the orders. So not surprisingly we got to the soldier’s post on Shuhada Street and were turned back. Now just for a minute, imagine you are a white American and you are walking down the street with your black American friend and a police officer tells you your black American friend can not walk down this street because he is black. Now remember that Israel considers this area of Hebron to be its territory, thus it is part of the middle east’s only democracy (!)

For a detailed map of these closures, see this map created by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

So we took the long way, through the old city, and were stopped a second time by six soldiers who asked for my passport and his ID.

After about 20 minutes we arrived at a turnstile, erected by the army, in front of Firas’s house. We went through and were immediately stopped by two soldiers who asked what we were doing.

Firas told them this was his house and he wanted to go inside.

The soldier asked why the family no longer lives there. At this point I was hoping Firas would tell the soldier about how settlers who lived across the street in the illegal and subsequently evacuated Beit Shapiro settlement would regularly try to break into their home, throw rocks at their windows, how the family had to install an industrial strength door and lock to prevent this, about how settlers set the building next door on fire, how settlers attacked them when they came and went from school, about how they had to show their IDs to the soldiers and prove that they lived there in order to enter their home everyday, how visitors were detained in the same manner and usually refused entry, and how the final straw was when Firas’s 18 year old sister Bashaer tried to come home from school one day. Settlers had congregated at the entrance to the apartment and told the soldier on duty not to let her enter the house. The soldier complied with their orders and told Bashaer she could not enter and that she had to go back. She refused and the soldier pushed her and kicked her. Her father watched the whole situation happen but of course he was powerless to do anything. They decided after that incident to leave. I was hoping Firas would tell the soldier these stories, but at the same time I knew it would not get him what he wanted, which was to enter his house. If you tell a soldier something like that, even if he knows it is the truth, you can pretty much forget about him being reasonable after that.

We waited around for an hour and a half for the soldiers to obtain permission from the DCO (District Command Office) to let us enter the house. I don’t know if it actually took this long to obtain the permission or if the soldier was just making us wait as part of some nebulous set of orders to make life for Palestinians in Hebron difficult. I’ll skip the political discussions I had with him, except for this part:

soldier: Where are you from ?

me: from the United States.

soldier: Are you Jewish ?

me: yes

*soldier has a look of surprise on his face*

me: What’s wrong, you’ve never hear of a Jew and a Palestinian being friends ?

soldier: No.

me: You don’t have any Palestinian friends ?

soldier: No.

me: He hasn’t tried to slit my throat or push me into the sea.

soldier: Yet.

In the end, the soldier told us we could enter the house for 15 minutes but the soldier would keep Firas’s ID until we came out and left.

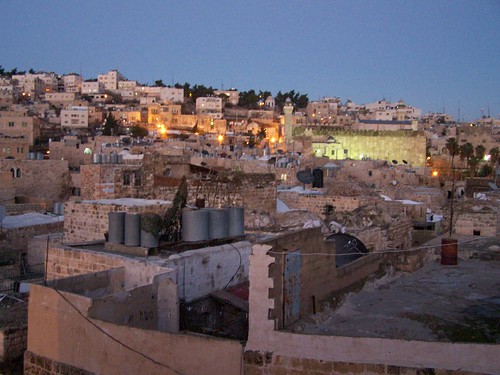

The house was pretty trashed, not surprisingly. The roof has a lovely view of the Ibrahimi mosque and the old city. It was sad. We looked around for a bit and took some photos and video. Then we left. I don’t know when he will be able to go back there and live again.