Tag: Hebron

-

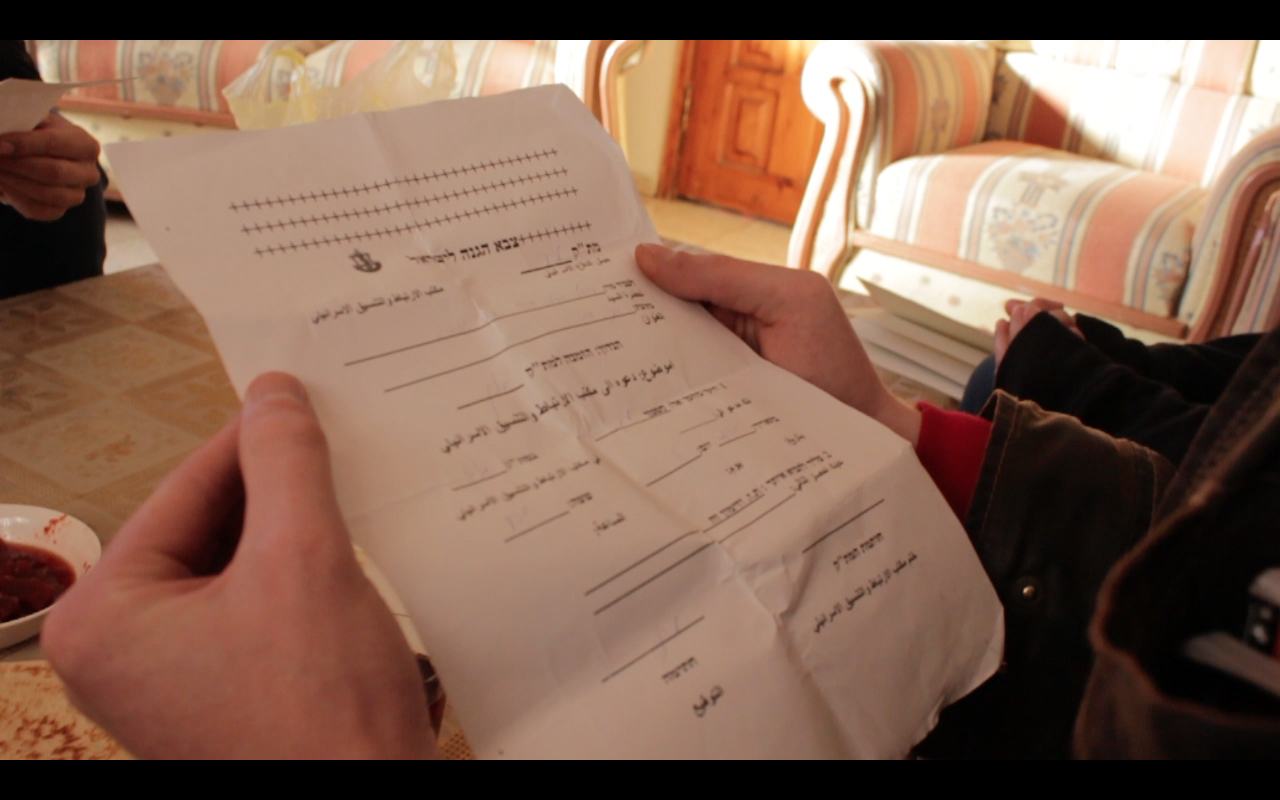

“We will hit your wife, your daughter, and your kids”

22nd January 2015 | International Solidarity Movement, Khalil Team | Beit Ummar, Occupied Palestine Early Tuesday morning January 20, 2015 at 3:00 AM, Israeli occupation forces invaded the home of the Abu Maria family in the village of Beit Ummar. The occupation army used explosives to open the front door, surprising the sleeping family. This…

-

Israeli forces detain a child and destroy four structures in the South Hebron Hills

21st January 2015 | Operation Dove | South Hebron Hills, Occupied Palestine On January 20th, Israeli forces detained a Palestinian child near the village of Maghayir Al Abeed and demolished four structures in the Palestinian village of Ar-Rifa’iyya in the South Hebron Hills area. At about 9.00 a.m. Israeli bulldozers started to tear down two houses and two…

-

Israeli forces weld shut the doors of an elderly Palestinian woman’s houses on Shuhada Street

19th January 2015 | International Solidarity Movement, Khalil team | Hebron, Occupied Palestine This afternoon in occupied al-Khalil (Hebron), Israeli forces gathered on Shuhada street, surrounding the doorways to the two houses belonging to Aamal Hashem Dundes, an elderly Palestinian woman, and her family. A soldier, wielding a torch and various other equipment, welded shut the doors.…