Tag: Gaza

-

International Solidarity Movement Committed to Staying in Gaza

18 April 2011 | ISM GAZA Arabic follows English — البيان مترجم للغة العربية Following the murder of our comrade and friend Viktor, we, activists of the International Solidarity Movement, would like to reiterate our commitment to remaining in Gaza. We will continue to work with and live among the Palestinian population as we continue…

-

Launch of international boat to monitor human rights in Palestinian waters

17 April 2010 | Civil Peace Service Gaza On Wednesday April 20th, the “Oliva”, a human rights monitoring boat with an international crew, will launch from the port of Gaza City. The crew of the Civil Peace Service, which currently consists of citizens from Spain, the United States, Italy and Belgium, will accompany Gazan fishermen…

-

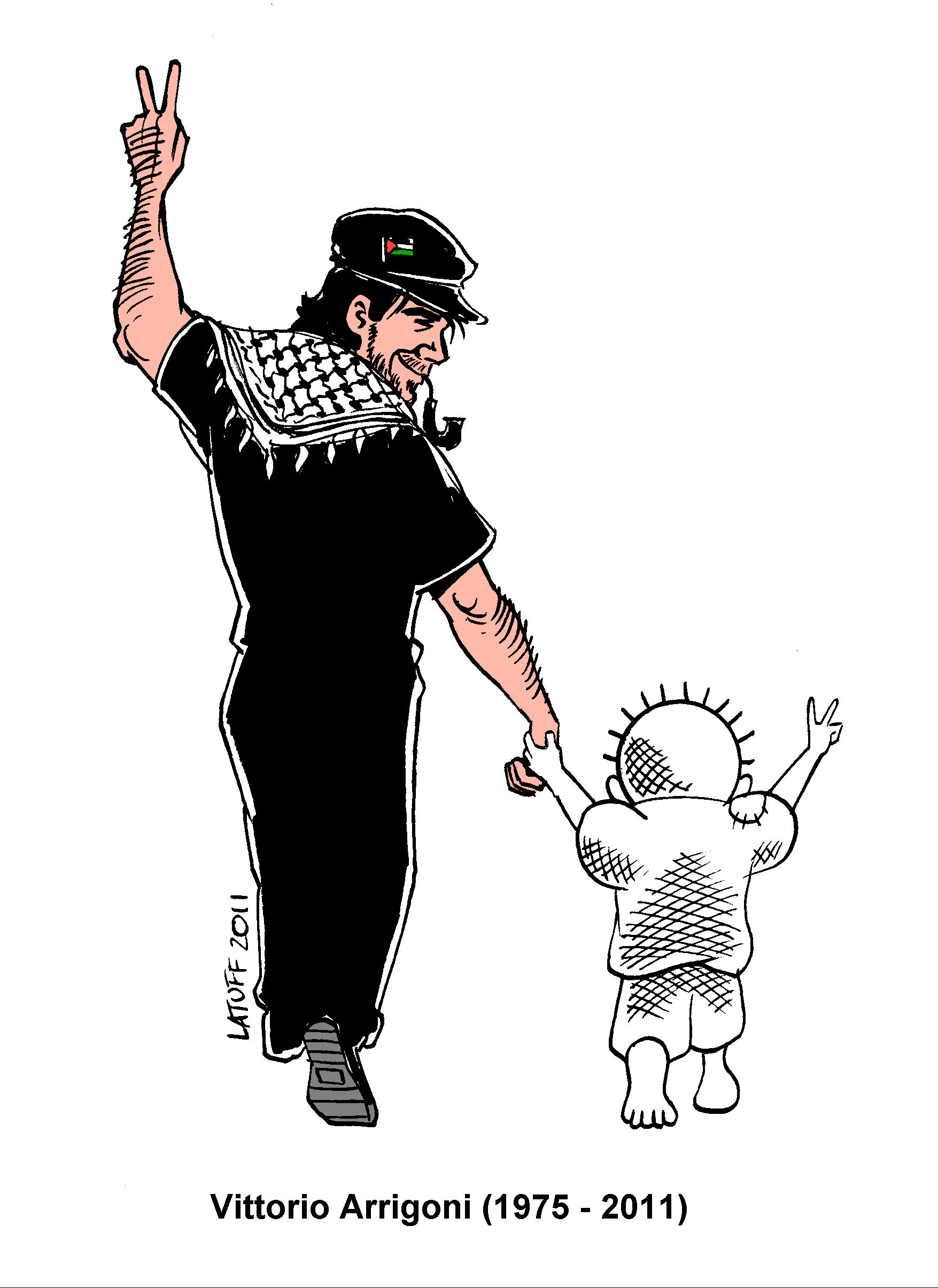

Solidarity Statements in honor of Vittorio Arrigoni

Organizations throughout Palestine and around the world are honoring Vittorio Arrigoni’s life and his work for the liberation of the Palestinian people. Collected here are some of those statements. If your organization is planning to issue a statement, please send it and any related URL to palestinesolidarity [at] gmail.com.