Category: In the Media

-

Russell Tribunal on Palestine finds Israel guilty of the crimes of apartheid and persecution

by Dr. Hanan Chehata 7 November 2011 | Middle East Monitor The Russell Tribunal on Palestine and its eminent panel of jurists has determined that Israel’s practices against the Palestinian people are in breach of the prohibition of apartheid under international law. Following two intense days in Cape Town listening to testimony from expert witnesses, the…

-

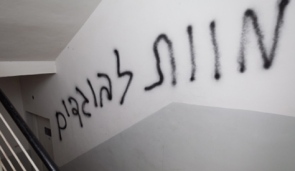

Jerusalem offices of Peace Now evacuated after bomb threat

by Oz Rosenberg 7 November 2011 | Haaretz Anonymous attackers spray-painted “price tag” and threatened to plant a bomb in the Jerusalem offices of “Peace Now” on Sunday. Hagit Ofran, director of Peace Now’s Settlement Watch project, said that at around 8 P.M., the office intercom buzzed and a man’s voice said, “The building will…

-

Freedom Waves prisoners abused and imprisoned; ‘Anonymous’ hackers strike back

by Ben Lorber 7 November 2011 | Mondoweiss In the immediate aftermath of the illegal capture of the Freedom Waves flotillas, Israel’s public image has been tarnished, as reports of violence at sea surface to counteract its claims of a peaceful takeover, and as human rights cyber-resistance group Anonymous retaliates by shutting down Israeli government…