Category: Journals

-

What will Gaza’s Ark face from the Israeli navy as it challenges the blockade?

17th April 2014 | International Solidarity Movement, Charlie Andreasson | Gaza, Occupied Palestine The heavy bang is heard clearly, and I have to resist the impulse to climb over the breakwater to try to get a view of the attack in the haze. And a new round of bangs is heard. It can’t be far off…

-

The fight for the freedom of the 5 Hares Boys continues

6th April 2014 | International Solidarity Movement, Nablus Team | Occupied Palestine In a conversation with Neimeh and Yaseen Shamlawi in their home in Hares we hear about the traumatic journey they have gone through but also the painstaking efforts they have made to build a campaign for their son’s freedom ever since he was arrested…

-

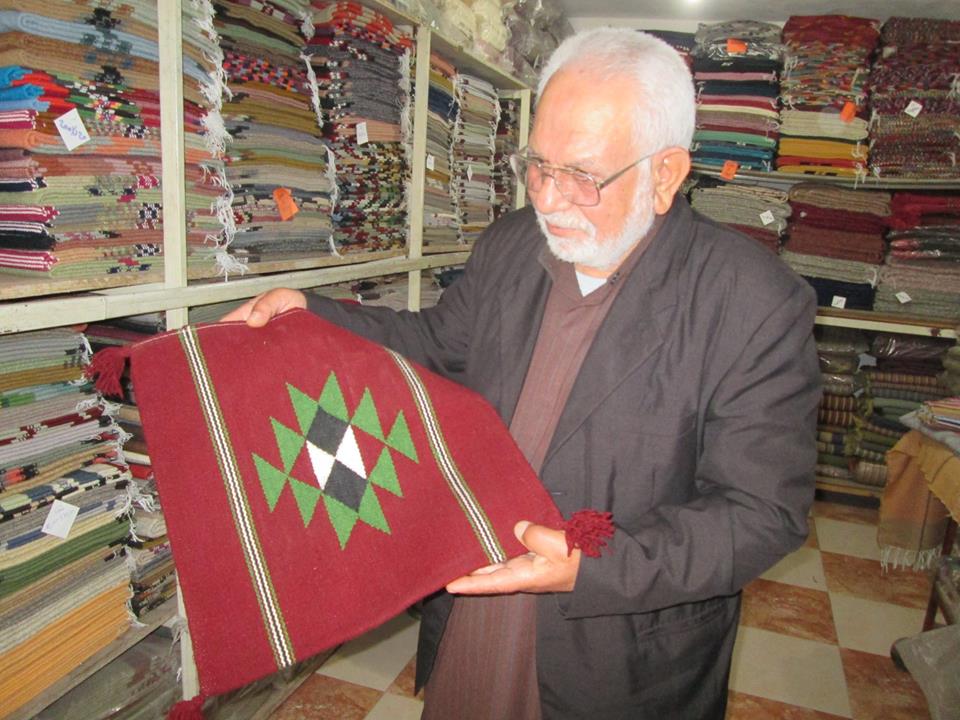

“The reason is to wipe out Palestinian culture and history”: A Gaza carpet factory under siege

28th March 2014 | International Solidarity Movement, Charlie Andreasson | Gaza, Occupied Palestine Before we settle down for a glass of Turkish coffee among shelves filled with neatly stacked, woven carpets Mahmoud El Sawaf, 68 years old, shows me around the small factory. The tour goes pretty quickly. There ‘s only a mechanized loom and a manual one. The…