July 18 | Yumna Patel | Mondoweiss

In less than 24 hours, 42-year-old Ismail Obeidiya, his wife Nida, and their six kids, could be made homeless. It’s a terrifying reality that Obeidiya is struggling to grapple with, his unease and frustration more palpable with every word.

“We fought so long and so hard, for years, to try to save our home. But in the end, the Israeli courts, the ‘High Court of Justice’ as they say, could not offer us any justice,” Obeidiya told Mondoweiss from the front yard of his home.

The Obeidiyas’ home is one of 10 buildings slated for an unprecedented mass demolition by Israeli authorities in the occupied East Jerusalem town of Sur Bahir.

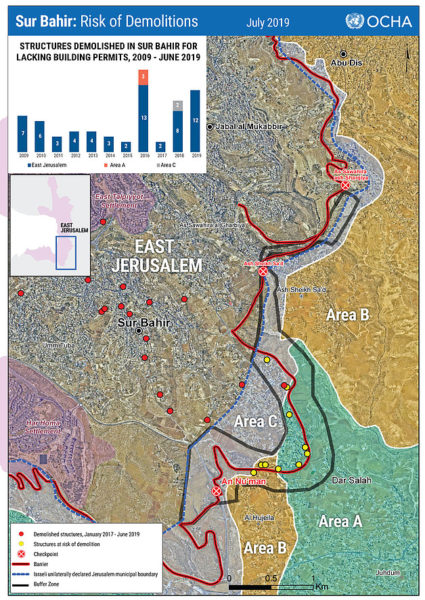

While Israeli demolitions of Palestinian homes in East Jerusalem are commonplace, typically under the pretext that the homes were built without Israeli-issued permits, the homes in question stand on ‘Area A’ and ‘Area B’ land under the control of the Palestinian Authority (PA), as designated by the Oslo Accords.

While most of Sur Bahir is located inside Israeli-annexed East Jerusalem, the area that Obeidiya lives in, called Wadi al-Hummus, borders the Green Line and is technically a part of the West Bank; but when Israel began constructing the Separation Wall in the area in 2005, the barrier was routed around Sur Bahir so that Wadi al-Hummus was annexed into the Israeli-controlled Jerusalem side of the barrier.

Despite the fact that residents of the area duly obtained building permits from the PA, Israel has continued to move forward with orders to demolish the homes on the grounds that they violate a 2011 Israeli military order prohibiting construction within a 100-300-meter buffer zone of the separation wall.

“I chose this area to build my home because it’s Area A, we thought this would protect us,” Obeidiya told Mondoweiss. “Contrary to what they say — we are here legally. Their demolition orders are illegal.”

Last month the Israeli Supreme Court denied a 2017 petition filed by Obeidiya and his fellow residents to save their homes, ending a seven-year legal battle in Israeli courts.

One week later, the court issued a notice to residents saying that they had one month, until July 18th, to demolish their homes. If they did not do so, Israeli authorities would demolish the homes for them, and send the residents the bill for demolition fees.

Should Israel follow through with the demolitions, local and international officials fear it could pave the way for Israel to enforce widespread demolitions in PA-controlled border communities across the West Bank and East Jerusalem.

“This will set a dangerous precedent for the Israeli occupation to take control of this area and others like it,” Hamada Hamada, 54, a local activist in Wadi al-Hummus told Mondoweiss, expressing fears that Israeli authorities will try to enforce similar measures across the occupied Palestinian territory.

“If these demolitions go through, all Palestinian towns on the border lines, close to settlements — basically anyone living on any land Israel wants, even if it’s controlled by the PA, they will be in danger and under threat.”

International attention

The case of Sur Bahir and the residents of Wadi al-Hummus has drawn widespread international attention in recent weeks, given the political gravity of the situation.

According to UN OCHA, if the demolitions are carried out, they would result in the displacement of three households, comprising 17 people, including nine children. Some 350 people whose homes are still under construction would also be affected.

“Additionally, residents fear a heightened risk of demolition of some 100 buildings that were built after the 2011 military order in the buffer zone in Sur Bahir,” UN OCHA reported.

Dozens of Palestinian, Israeli, and European officials descended upon Sur Bahir on Tuesday at the behest of residents and local activists in a last-ditch effort to save their homes.

Diplomats from some 20 countries toured Sur Bahir, visiting the 10 buildings — comprising 70 apartments — slated for demolition as per last month’s Supreme Court order. All but one of the buildings, some of which are still under construction and uninhabited, are located on the Jerusalem side of the wall.

One of the residents to speak to the officials was Obeidiya, who urged the international community to intervene on behalf of him and his neighbors, telling them that him and his family would be left on the streets if their home was demolished.

During the tour, the French consul general for Jerusalem, Pierre Cochard, told journalists “he did not think the security explanation provided by Israel was sufficient to move ahead with the move,” the Times of Israel reported.

“I think it’s important to underline that we cannot deny their right…they are here in Palestinian territory,” Cochard said.

One of the officials present was Israeli MK Ofer Kasif of the joint Israeli-Palestinian left-wing Hadash party. “I came here today to show my support and stand with all the Palestinian families whose homes are under attack and threat of demolition,” Kasif told Mondoweiss.

“The current Israeli government has opened a war against all the Palestinian people. Home demolitions are one part of all of the things they are doing. They have one goal, to kick all the Palestinians out of their homes,” Kasif said.

The Palestinian Liberation Organization released a report on the situation in Sur Bahir, urging the international community to move beyond “mere condemnations,” and take direct action against the Israeli government for its policies against Palestinians in the occupied territory.In a statement on Wednesday, several UN officials called on Israel to immediately halt its plans to demolish the structures in question, and to instead “implement fair planning policies that allow Palestinian residents of the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, the ability to meet their housing and development needs, in line with its obligations as an occupying power.”

“Israeli breaches of international law and violations of Palestinian rights, necessitate urgent action by the international community,” the report said, adding that “without accountability, Israeli impunity will prevail.”

Dividing Sur Bahir

Crucial to understanding the current fight in Wadi al-Hummus, is to understand the geography of Sur Bahir, how its land has been divided over the years, and the effects it has had on the local community.

With an estimated population of 24,000 Palestinians, Sur Bahir is one of the largest Palestinian towns in East Jerusalem, situated around 4.6 kilometers southeast of the Old City.

While the total original land area of Sur Bahir is around 10,000 dunums (approx. 2,471 acres), much of the town’s land has been confiscated by Israel over the years for the use of settlement construction, settler bypass roads, and the separation wall.

Following the Israeli occupation of East Jerusalem and the West Bank in 1967, Israel illegally annexed some 70,000 dunums of Palestinian land and extended the boundaries of the Jerusalem municipality to dozens of Palestinian towns along the border, including most of Sur Bahir’s land.

In 1995, under the Oslo Accords, the remaining eastern neighborhoods of Sur Bahir that were not officially under the Jerusalem municipality — Wadi al-Hummus, al-Muntar, and Deir al-Amoud — were classified as PA-controlled land, split up into Areas A, B, and C.

When speaking to Mondoweiss Hamada broke down the 10,000 dunums of Sur Bahir land into the following categories:

- An estimated 1,700 dunums have been confiscated for the construction of nearby Israeli settlements

Some 4,800 dunums were classified as being under the control of the Jerusalem municipality. - Out of those 4,800 dunums, the municipality has allocated only 1,500 dunums for the construction of homes. The majority of Sur Bahir residents live in this area.

- The remainder of the land in Sur Bahir, approximately 3,500 dunums, is PA-controlled land, where Wadi al-Hummus is located. Some 6,000 Palestinians live there.

- For decades residents of Sur Bahir, like many other Palestinians living in communities bordering Jerusalem and the West Bank, were forced to navigate the complex network of zoning and housing laws.

Despite some residents technically living in Jerusalem, and others living in the West Bank, the community remained unified, with the majority of them holding permanent residency in Jerusalem.

When Israel began construction of the wall in 2004, the community was faced with another problem that threatened to complicate their lives even further.

“The original planned route of the wall was to cut directly through Sur Bahir, between the separating the Jerusalem municipality area from the West Bank area of the village,” Hamada told Mondoweiss. “But the people didn’t want this, so we protested and protested against the construction of the wall.”

It was only after then US National Security Advisor Condolezza Rice intervened, that Israel changed the route of the wall to be placed further north, effectively annexing the West Bank part of Sur Bahir onto the Israeli-controlled side of the barrier.

Even though the residents “won” their battle to have the route of the wall changed, Hamada says that its construction has still caused irreversible harm to the fabric of the community.

Living in limbo

After the construction of the wall, despite being physically separated from the West Bank and put on the Jerusalem side of the barrier, the areas of Wadi al-Hummus, al-Muntar, and Deir al-Amoud and their residents have not been incorporated within the municipal boundaries.

“It’s like we are living in limbo,” Hamada told Mondoweiss. “We are legally under the jurisdiction of the PA, but the Israeli government does not allow the Palestinian to exercise its authority beyond the wall.”

“We are living in Areas A, B, and C, and thus, everything from the permission to build, paving roads, electricity, water, etc. should all be under the responsibility of the PA,” he continued. “But the wall doesn’t allow the Palestinian government to fulfil any of their responsibilities to the people.”

While the Israeli government does not allow the PA to service these areas, the Jerusalem municipality also refuses to provide services because the areas are technically outside the boundaries of the municipality.

With no one one to protect them, residents of Wadi al-Hummus and the other PA-designated areas of Sur Bahir have been subject to widespread attacks from the Israeli government.

According to UN documentation, since 2009, “Israeli authorities have demolished, or forced owners to demolish, 69 structures in Sur Bahir, on the grounds of lack of building permits, of which 46 were inhabited or under-construction homes,” resulting in the displacement of some 400 Palestinians.

With the issuance of the Israeli military order in 2011, hundreds more homes in Areas A, B, and C, despite already have building permits from the PA, were put under threat of demolition due to their proximity to the wall.

“The buffer zone includes more than 200 buildings, of which about 100 were built after the 2011 military order, according to local sources,” UN OCHA reported.

During their conversations with Mondoweiss, both Hamada and Obeidiya stressed the fact that the demolitions would not just cause families to lose their homes, but so much more than that.

“With these demolitions, people’s entire lives will be destroyed, all the money that they saved and spent on building their dream homes will be crushed,” Hamada said.

Obeidiya says he is more than 400,000 shekels (approx. $112,940) in debt between building costs, lawyer fees, and Israeli fines.

“We are absolutely devastated. I worked for years to build a home for me and my family, a future for me and my kids,” Obeidiya told Mondoweiss. “But the Israeli occupation has destroyed us, not just our homes. They are slowly killing us.”

Published in Mondoweiss on July 17