15th April 2014 | Paramedics in Gaza | Gaza, Occupied Palestine

Yesterday I visited the Civil Defence Directorate, which provides the fire and rescue service in Gaza, as well as some emergency ambulances and marine rescue. These guys have a reputation as being fearless, as well as being the most vulnerable to attack during times of war. In the 2008-9 war, 13 Civil Defence workers were killed in the line of duty, with 31 injured. This includes medics killed in their ambulances by snipers and firefighters injured by secondary drone attacks while rescuing victims of the initial strikes. These risks are additional to jobs which are considered dangerous even in peaceful countries like the UK and USA.

I found out plenty about the Civil Defence’s ambulance service, including interviewing staff and looking around the ambulances and equipment stores, but I’m going to save that for a later post and just write about the firefighters. In the UK, the ambulance service and fire service are separate so please forgive any ignorance about the equipment and vehicles I saw. I knew they were fire engines because they were big and red, and I knew it was a fire station because there were some weights in the corner and a ping pong table. Beyond that, it was all new to find out. Let’s start with a familiar theme in Gazan emergency services: shortages. After meeting with the Red Crescent and Department of Health, looking around a few dozen ambulances, an Emergency Department and interviewing a variety of health care workers, I’ve seen the same issues occurring endlessly. No equipment, limited or no drugs, no electricity, expensive fuel, training problems and unacceptable risk in times of conflict. The impact of each issue varies according to the service (for example, the electricity cuts are a huge problem for Al-Shifa hospital, whereas the fuel crisis has more of an impact on the emergency services) but the end result is the same – hamstrung services and an impossible situation for managers and workers.

I met with Yousef Khaled Zahar, the general manager of the Civil Defence, who broke down the issues facing his service while we drank sugary coffee. Firstly, the fire service vehicles are old and outdated – ‘every day the vehicles age’ as Zahar said. They are mostly from 1988/89, meaning their safety features are wildly outdated. Half of their fleet were destroyed during Cast Lead, with little chance of replacements reaching Gaza. Since then they have done some pretty unreal mechanical work to keep vehicles on the road despite the lack of spare parts. They have also converted some old Kamaz trucks into fire service vehicles – they have welded water tanks including internal baffles from scratch then installed them on the back, plus the water pumping mechanisms and other necessary machinery. Then it’s all been painted red.

It was astonishing to see the creativity and technical skills behind these vehicles, and the solutions that they’ve found with such limited resources. They’re far from ideal compared to a purpose-designed vehicle – the centre of gravity is dangerously high because of the position of the water tank – but they help to keep the ambulance service functioning. They were previously only used to resupply fire engines, but after some water pumps were found that could run off a spare drive shaft, they are now used as fire engines themselves. Additionally, the fire service had issues getting a steady supply of expensive foam for fighting fuel fires, so they designed their own foam that can be made locally for 10% of the cost. The workers in the fire service workshops and garages must be some of the most resourceful and creative engineers in the profession, and they seem deeply valued by their managers and the firefighters themselves. As I mentioned earlier, fuel is a huge issue for the emergency services and especially the Civil Defence. The fire engines are amongst the biggest vehicles in Gaza, so restricted fuel supplies have a magnified impact. In the past, much of their fuel came through the tunnels from Egypt along with firefighting equipment, protective clothing, vehicle parts, medicines and medical disposables. Since they were destroyed last year, none of these things can get through. Fuel costs are now the largest part of their budget – a massive issues considering that their staffing levels are at 40% of what is needed due to lack of money for wages. They’re looking into alternative fuels at present, but the current situation is dire.

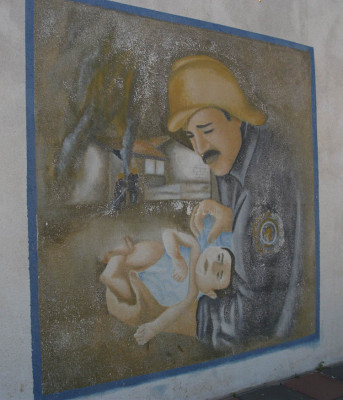

After talking, Zahar took me around the Civil Defence centre, which is their administrative centre as well as an ambulance and fire station. We looked in on the medical clinic and dentist who provide cheap care for employees and their families. They offered me a dental check up while I was there – admitting to a load of tough firefighters that I was scared of dentists wasn’t my proudest moment. To finish my visit I interviewed a Mohammed, a firefighter pushed forward by his colleagues as the one who liked to talk the most. Happily, the rest of his watch also came and sat with us and added alot to the conversation. Their hard-won camaraderie was strong and humbling to be around. Mohammed has been a professional firefighter for four years, after previously working as a volunteer. He wanted to be a firefighter since he was a kid, a vocation fortified by growing up amid the volatility of Gaza. His favourite part of the job is when they reach a scene, enter and are able to rescue people. He described the feeling of rescuing children, and his family’s pride in his work. We talked about the relationships between firefighters, who work in a watch system similar to the UK. At this point others joined the conversation, describing each other as brothers and friends. They talk about how they enter a scene together and stay together in the risk, knowing that they can rescue each other and be rescued themselves. They have families who worry about the risks of their job but know they can’t prevent them from doing this work – but they also have a second family at work, and a second home on station.

Nearly every one of the ten or so people I talked with had been injured while working, including the general manager Yousef Khaled Zahar. Mohammed was seriously injured when he and other firefighters entered a family home after a drone attack to rescue the family. A secondary attack hit the house and the firefighters were caught in the explosion. He was left unconscious, and while he has recovered, his chest injuries mean that he is still missing ribs. He and other injured colleagues says the decision to return to work was not a difficult one – they knew the risk when they joined, and know they can die at any time. Firefighters who are not physically able to return to work are given desk jobs in the Ministry of the Interior.

The targeting of the emergency services in Gaza has been systematic and brutal. During Cast Lead, Civil Defence buildings were specifically targeted in airstrikes that caused $2.5m of damage. The station that I visited was occupied by tanks, forcing fire crews to continue responding from the street. Rows of bullet holes remain across the front of the station. Gazan infrastructure is repeatedly considered a valid target in Israeli airstrikes, including the emergency services. This is an intolerable situation, putting the lives of firefighters, rescuers and medics at risk while they work to preserve life. I asked the firefighters I met yesterday if there was anything they’d like to add to our interview. Firstly one of them said ‘If we die here in our service, we will die in peace. This does not stop us working’. They then spoke together to ask that international emergency workers try to defend and protect them in the case of another war. They know that international law should protect them, but they also know from direct experience that in reality it does not. Yet they continue to work in what must be one of the most dangerous jobs in the world, motivated by the desire to rescue and protect their community. They need better vehicles, more staff, safer working conditions and better protective equipment to do their jobs. But most of all they need the protection they are entitled to as rescue workers, and they need our solidarity.

Many thanks to the management and staff of the Civil Defence for their time and hospitality. As ever, most conversations were had via a translator, creating some margin of error. Big thanks to Fady for translation and coordination, and to this article by Joe Catron for additional statistics and information.