Eyal Weizman interview: Israel’s oppressive architecture of occupation

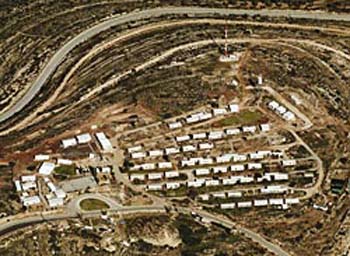

The Migron settlement

Dissident architect Eyal Weizman explains the mechanics of Israel’s occupation of Palestine to Anindya Bhattacharyya

The occupied West Bank, 1999. A group of Israeli settlers complain that their mobile phone reception cuts out on a bend in a road from Jerusalem to their settlements.

The mobile phone company Orange agrees to put up an antenna on a hill overlooking the bend.

The hill happens to be owned by Palestinian farmers, but since mobile phone reception is a “security issue”, the mast construction can go ahead without the farmers’ permission.

Other companies agree to supply electricity and water to the construction site on the hill.

In May 2001 an Israeli security guard moves on to the site and connects his cabin to the water and electricity mains. Then his wife and children move in with him.

In March 2002 five more families join him to create the settler outpost of Migron. The Israeli ministry for construction and housing builds a nursery, while donations from abroad build a synagogue.

By mid-2006 Migron is a fully fledged illegal settlement comprising 60 trailers on a hilltop around the antenna, overlooking the Palestinian lands below.

This blow-by-blow account of just one example of the ongoing Israeli colonisation of Palestine appears in the opening pages of a fascinating new book by Eyal Weizman, the dissident Israeli architect.

Called Hollow Land: Israel’s Architecture of Occupation, it is an extraordinarily detailed account of exactly how the occupation works in practice, focusing on the physical organisation of space and the political dynamics that shape it.

The 300 page book is packed with fascinating diagrams and photographs that shed a revealing light on almost every aspect of the occupation.

Housing

It explains the way that housing projects in Jerusalem are clad with a specific kind of stone to give the houses a “Biblical” look, and the use of one-way mirrors at border posts in the West Bank.

Eyal Weizman started work on the book in 2001 when he was commissioned by B’Tselem, the Israeli human rights organisation, to help document how Palestinian rights were being violated through the planning of Israeli settlements in the West Bank.

This work was later turned into an exhibition and book called A Civilian Occupation. The Israeli Association of Architects commissioned the project – only to prevent the exhibition from being shown and then destroy 5,000 copies of the book.

Today Eyal Weizman lives and works in London as director of the Centre for Architectural Research at Goldsmiths College.

His students work on a variety of similar projects that combine architectural and political analysis, including studies of Dubai, Beirut and United Nations protectorates in the former Yugoslavia.

I asked Eyal what had prompted him to write the book – and what the significance was of its subtitle referring to the “architecture of occupation”.

“As I was working, it seemed to me more and more that the entire occupation, the entire formation of the terrain itself, could be thought of in the same way as you think of the structure of a building,” he says.

“This first occurred to me while reading the Oslo Accords of 1993. The partition of the territory put forward there is not two dimensional but three dimensional – it partitions a volume, rather than a land, giving Palestinians some bits of land while maintaining the subterranean water reservoirs and airspace for Israel.

“As soon as you imagine geopolitics operating in a volume like that, architecture comes into play.”

This analogy led him to consider how architectural analysis could be applied to a military and political situation: “For instance, what’s the most basic analytic tool you use if you’re an architecture student and you want to understand a building? You draw a cross-section through it.

“In fact, the book Hollow Land is structured as a cross-section through the entire Occupied Territories. The first chapter is about the underground water reservoirs.

“Then it looks at the archaeology, then the valleys, the hills and finally the airspace. It’s a series of episodes that make up a volume, layer by layer, chapter by chapter.

“So you can think of the entire occupation as if it was some kind of complex building, such as an airport or a shopping mall, with security corridors inbound and outbound, and movement through it.”

This focus on the material organisation of Israel’s encroachment into the West Bank might sound rather dry – but in fact Hollow Land’s relentless and patient accumulation of details throws the human catastrophe of the occupation into even starker light.

One particularly chilling section of the book discusses Israeli military techniques for sending assassination squads into the dense urban sprawl of Palestinian settlements.

Rather than use the alleyways and paths of the settlement – and risk ambush – the Israeli soldiers simply blast their way in a straight line through to their target. They cut holes in the walls of residential buildings and literally march straight through people’s living rooms.

To train the occupation troops the Israelis have built a fake Palestinian settlement in the Negev desert – whose buildings are ready equipped with holes cuts into their walls. The US has now started building similar fake villages to train its troops for the occupation of Iraq.

Hollow Land does not just document the shape of the Israeli occupation – it also looks into the dynamics that created that shape in the first place. “It’s about the way in which politics, culture and other formative forces register themselves in the organisational form of the landscape,” says Eyal.

“The idea is that you look at a piece of architecture, or any piece of design, and study it as a consequence of conflicts, forces, practices and so on. So form becomes a kind of diagram of the forces that create it – process is frozen into form.”

One example of this is the Migron settlement described at the beginning of the book, which arises out of the interplay of a whole host of actors – Israeli settlers, mobile phone companies, utility firms, state institutions, the army and so on.

Eyal is keen to stress how “settlements emerge out of organisational chaos”. The very nature of the occupation is one of “uncoordinated coordination”, where the government allows degrees of freedom to rough elements and then denies its involvement. He says this is characterised by “micro-processes that become wheels in larger processes”.

The wall

A key example of this is the construction of the “separation wall” in the Occupied Territories – a huge barrier designed to wall off the Palestinians into tiny enclaves while annexing vast portions of the West Bank for Israel.

The wall is fiercely controversial even within Israel, and its precise route is constantly being contested. As a result the wall snakes through the West Bank in a curiously fluid manner, sometimes swinging out east to take in an illegal Israeli settlement, at other times being pushed back west again.

“The trick is to understand how the wall is flexible without justifying it as benign – it’s a dangerous flexibility!” says Eyal.

“But what the course of the wall registers the most is opposition to it – the constant petitions of Israeli NGOs to the Israeli high court of justice and the weekly demonstrations by Israeli human rights groups, for instance.”

In a striking analogy, Eyal suggests that the space of possible routes of the wall maps the spectrum of official Israeli politics – the doves seeking a wall to as close to Israel’s pre-1967 borders as possible, the hawks wanting to push the wall out towards Jordan.

The wall’s route reflects the dynamic between these two forces.

But for Eyal the problem is that fierce battles over the precise route of the wall can fail to challenge the wall’s very existence.

“These micro-political acts of resistance are paradoxical because by pursuing the lesser evil they allow the greater evil of the wall to exist and function,” he says. “The opposition to the wall becomes part of what designs it – it becomes complicit in the wall.”

Eyal argues that this paradox is part of a larger pattern whereby the occupation has absorbed and incorporated the views of the human rights organisations and NGOs at work in the Occupied Territories.

Human rights

“In some cases human rights organisations end up influencing the design plans for checkpoints,” he notes.

“They end up sustaining the occupation. They go to the military and plead for certain things. Governance always needs carrots and sticks – it operates not just on the basis of threats, but by absorbing the opposition into a governing system.”

One example of this is the fact that Palestinians in Gaza are dependent on food aid from international donors.

“If humanitarian organisations did not feed Palestinians in Gaza there would be a crisis – some 1.8 million Palestinians live off international aid,” he says.

“Consequently a significant part of Israeli intelligence is to monitor the levels of hunger in Gaza and keep it just at the level that the world will tolerate. This level changes – a level of hunger that would not have been tolerated in the 1990s is tolerated now.”

Eyal is aware that this might sound “anti-humanitarian” but he insists he is not suggesting that NGOs should simply down tools and leave the Palestinians to their fate.

Rather it’s a matter of a clear sighted acknowledgement that even the best intentioned and most benign of humanitarian organisations operating in the Occupied Territories is to a certain extent complicit, and, to a certain extent, part of the problem.

Ultimately Eyal says he is pessimistic over the current prospects for Palestinians. He believes the madness and terror of the occupation stem out of the paradoxes of trying to partition the land in the first place into separate “Israeli” and “Palestinian” territories.

“You have to understand the idea that guides the Israeli occupation, which is how to resolve the paradox of maintaining overall control while ensuring separation,” he says.

“It’s very different from other kinds of colonial geography – for instance, the ‘bantustans’ in apartheid South Africa were special designated zones, but with Israel and Palestine you get overlapping claims over the same sites woven together into mutually exclusive separate networks that try to never cross.”

This pattern of settlements and camps arranged in space, connected by bridges and tunnels, has a long history. “This is something you get from the very first attempt to divide Israel and Palestine,” Eyal notes.

“If you look at plans from the 1920s and 1930s prepared for the League of Nations during the mandate period by diplomats and mapmakers, you’ll see that nobody could find a line that separates Israel from Palestine – it was always a matter of building bridges or tunnels over or under the other’s territory to maintain continuity.

“So my critique throughout the book is against the politics of partition. I want to show how paradoxical partition is – and that it just cannot operate physically.”

—

Hollow Land: Israel’s Architecture of Occupation by Eyal Weizman is published by Verso and available from Bookmarks, the socialist bookshop, for £19.99. Phone 020 7637 1848 or go to www.bookmarks.uk.com

PIC CAPTION: The Migron settlement (Pic: Milutin Labudovic/Peace Now)

http://www.socialistworker.co.uk/art.php?id=12838